The steady decline of fertility rates in Australia presents a multifaceted challenge with wide-reaching implications for the nation’s social, cultural, and economic future.

Fertility rates are a critical indicator of societal health, influencing inter-generational stability, economic growth, and family dynamics. Sustained low fertility leads to shrinking workforces, increased dependency ratios, and growing financial pressure on public services such as healthcare and pensions. These systemic strains hinder productivity and innovation, making it imperative for Australia to address the factors contributing to its fertility decline.

At the heart of this issue is the growing gap between Australians’ aspirations for family life and the realities imposed by financial and systemic constraints – chief among them being housing affordability. Despite a consistent desire for family formation, young Australians are finding it increasingly difficult to achieve their ideal family size due to rising property prices and limited access to suitable housing. This phenomenon is reshaping Australia’s demographic landscape, particularly in major cities like Melbourne, Sydney, and Brisbane, where fertility rates have dropped to historic lows.

Australia stands at a pivotal moment, with its largest demographic cohort of individuals in their prime childbearing years poised to shape the country’s demographic future. Failure to implement meaningful policy reforms that enables access to affordable, family housing will only deepen the demographic and economic crisis for generations to come.

Fertility decline in Australia

Healthy fertility rates are fundamental to the functioning of society, influencing its cultural, economic, and social structures. It therefore follows that any prolonged decline will impact these systems, reshaping family dynamics and slowing national economic growth. As Richard Reeves, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution observed, ‘You don’t upend a 12,000-year-old social order without experiencing cultural side effects.’

As already evidenced in countries such as Japan and Italy, the economic impacts of sustained fertility declines are significant. As the workforce shrinks, the tax base needed to fund essential services like healthcare, pensions, and aged care diminishes, even as demand for these services grows due to an aging population. Over time, this strains resources and fosters systemic inefficiencies. With a reduced future labour force, economic growth slows, limiting innovation and productivity.

Furthermore, weakening birth rates erode inter-generational ties and increase dependency on government institutions to provide support that families once provided while undermining personal responsibility and individual rights. Any shift from family-based support to government dependence poses several risks and challenges, a concept perhaps best summed up by Ronald Reagan when he quipped that, ‘The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’

Separate to the societal effects of declining fertility, yet no less severe, is the more personal and deeply emotional impact associated with the profound grief being experienced by those facing involuntary childlessness. The subject of increasing research, childlessness often proves to be not only isolating but acutely painful, not just for the individuals directly affected, but also their parents who often grieve the absence of grandchildren. With childlessness on the rise, these impacts will only worsen creating long-term repercussions for family cohesion and societal well-being.

Given these far-reaching consequences, it is crucial to examine the factors driving fertility decline. While cultural and lifestyle shifts play a role, financial barriers – particularly housing affordability – have emerged as the dominant constraint on family formation.

How Australia’s affordability crisis is shrinking families

Contrary to popular belief, Australians overwhelmingly want to have children, with most aspiring to have at least two. Sufficient to maintain population replacement, this ideal family size has remained stable across generations and is consistent with international trends. Yet, despite this aspiration, a persistent and growing gap has developed between the number of children Australians want to have, and the number they do.

This shortfall is not the result of shifting personal choices but is increasingly attributable to financial and systemic barriers. Central among these is housing affordability, which plays a crucial role in family planning decisions.

Still considered the foundation of financial security and an important milestone before starting a family, rising property prices in Australia have made homeownership increasingly unattainable, particularly for middle and lower-income households, where the financial burden of buying a home is disproportionately felt. Lack of housing for young families, Nobel laureate economist James Heckman stated, depresses family formation and fertility.

The level of sensitivity between housing affordability and fertility rates is evident in research produced by the Bank of England, which found that a 1 percentage point drop in interest rates led to a 2 per cent increase in birth rates. The study demonstrated that even small reductions in mortgage costs can directly influence decisions about having children, as lower repayments ease financial pressures on families. In a country like Australia, where housing costs are a far greater burden, the effect is likely even more pronounced – meaning that rising mortgage repayments and ongoing affordability challenges could accelerate fertility decline.

Australia is now following the low-fertility, high-cost housing trajectory, and the consequences are already evident. Couples are having smaller families and taking longer to start them as fertility rates in Australia continue to fall. The greatest declines are occurring in the nation’s major cities, with Melbourne, Sydney, and Brisbane consistently reporting the lowest fertility rates in the country. This trend has become so pronounced, Peter Achterstraat, the New South Wales Productivity Commissioner recently warned that Sydney is at risk of becoming ‘a city with no grandchildren’ due to young families being priced out and forced to relocate.

In its report, The Impact of Policies on Fertility Rates, the Centre for Population identifies rising housing costs as a major obstacle preventing young adults from attaining homeownership before starting a family. With many forced to delay having children until they feel financially secure enough to buy a home, the report highlights declining housing affordability as a key reason why Australia’s low fertility rate is likely here to stay. As all five of the country’s mainland capital cities are now ranked amongst the 20 least affordable housing markets globally, the prospect of reversing this trend looks almost impossible.

The preference for family-friendly housing

Amid the worsening affordability challenges, the preference for detached housing remains strong among Australian families. Families seek space for raising children, which includes the need for additional bedrooms, larger living areas, and access to outdoor environments – amenities less available in high-density housing.

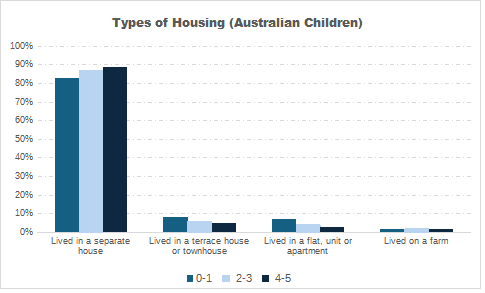

Data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children illustrates this trend, showing that most children live in detached houses, with this preference increasing as children grow older. It revealed that 83 per cent of children lived in detached houses as infants. By age 2-3, this increased to 87 per cent, and from age 4-5 onward, nearly 90 per cent.

Source: Australian Institute of Family Studies 2020

Across the globe, the detached house remains the most desired form of living, particularly by families. In the Netherlands – a nation often lauded for is its socially progressive values and revered pattern of dense living environments – couples frequently transition to single-family homes and homeownership just before or during pregnancy, highlighting a universal need for space and stability when raising a family.

Further underscoring this trend, while fertility rates in Australia’s most unaffordable cities – Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane – continue to decline, a post-Covid shift has seen fertility rates in many regional areas increase, returning to replacement level. This shift reflects a clear preference for more affordable, family-sized homes, reinforcing the argument that housing affordability is directly shaping family formation decisions.

Despite this, policy continues to overlook families’ preferences in favour of high-density urban development. Governments across Australia continue to restrict housing options and drive-up prices by persisting with urban containment and densification policies in pursuit of their own idealised version of city living.

Largely coinciding with those locations experiencing the greatest amount of high-density apartment development, the number of suburbs across Australia where fertility rates have dropped below one, is steadily rising. This highlights the degree of social, cultural, and economic resistance to apartment living by families with children. Beginning in the inner city, this phenomenon is now extending into middle-ring suburbs, particularly in Melbourne.

Limited access to affordable, family-friendly housing is a significant factor discouraging couples from starting families in these locations. That couples are less likely to have their first child in inner or middle-city areas because of smaller, more expensive housing remains completely overlooked by those responsible for housing policy. By relying heavily on the development of high-density housing, typically consisting of one- and two-bedroom apartments, stubborn attachment to containment policies ignores a crucial reality: that ‘couples with children’ are, and will remain, the largest household type in Australia for decades to come.

The opportunity ahead

Australia stands at a critical juncture in addressing its fertility decline. Though the ongoing housing crisis continues to suppress birth rates, the nation is uniquely positioned to reverse this trend. Over the next decade, Australia’s largest age demographic – those aged 30–39 – is set to grow, and within this group, women aged 30–34 consistently record the highest fertility rates. This convergence of favourable demographic trends presents a rare opportunity to take decisive action.

Strong families are the foundation of a thriving society. Without policies that support family formation, Australia faces a weakening of its social fabric and long-term economic security.

If policymakers align strategies to remove key barriers – particularly by improving access to family-friendly housing and providing targeted financial support – Australia can secure both sustainable population growth and long-term economic stability. However, the window for action is narrow. Without immediate reform, the opportunity may be lost, further entrenching the nation’s demographic and economic challenges. The success of countries such as Hungary shows that bold, well-designed policies can yield meaningful improvements. Australia has the potential to achieve the same – if it acts now.

Despite strong and consistent demand for family-friendly housing, affordability constraints are preventing many from achieving this goal. As a result, addressing housing affordability is not just about economic security – it is a crucial opportunity to reverse Australia’s fertility decline.

International lessons: the case of Hungary

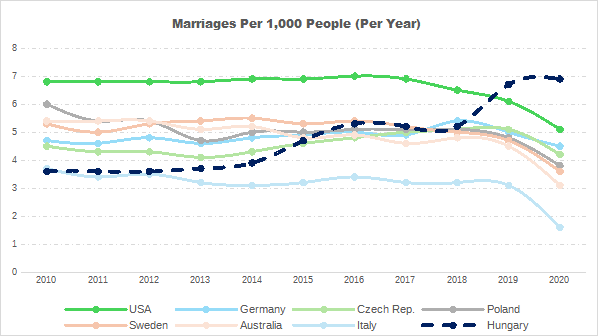

Hungary’s pro-natalist strategy offers valuable insights into the challenges facing Australia, demonstrating how targeted policies can counter declining birth rates by encouraging larger families. This approach aims to promote long-term population growth, economic sustainability, and social stability. Hungary’s fertility rate has shown one of the strongest increases globally, rising from just 1.23 in 2011 to 1.61 in 2021 – above the EU average of 1.53. Now the highest among OECD countries, this growth has been partly driven by Hungary’s rising marriage rate, a key predictor of future fertility. Public sentiment strongly backs these efforts, with 74 per cent of Hungarians supporting state involvement in family support policies, well above the EU average of 42 per cent.

A major factor behind Hungary’s success is its direct and substantial family support programs, which focus on preserving family structures and ensuring national sovereignty in a rapidly changing geopolitical landscape. These programs include financial incentives, housing grants, tax relief for larger families, and measures to strengthen family stability.

By linking support to both family formation and marriage, Hungary’s strategy extends beyond a simple fertility policy – it is a comprehensive family initiative. Its marriage rate is particularly remarkable, having steadily risen to become the highest in the OECD and which serves as a strong indicator of future fertility.

Source: Our World in Data

One of the most significant initiatives is the Family Housing Support Program (CSOK), designed to remove financial and physical barriers to family-friendly housing. Key features of the program include non-refundable grants, interest-free loans, and little to no income tax for families with three or more children. To ensure homes are suitable for raising children, the program also sets minimum size standards for properties funded through the scheme.

Hungary’s success demonstrates that fertility decline is not inevitable – it can be reversed with the right policy mix. In contrast, Australia’s housing crisis continues to suppress birth rates, making urgent reform essential to prevent further demographic decline.

Addressing fertility decline

Young Australians are not rejecting family life – they are being priced out of it. Without immediate action to improve housing affordability, the gap between desired and actual fertility will widen, deepening the economic and demographic challenges already facing the nation.

Enabling homeownership is not just about economic security – it is fundamental to supporting family formation, self-reliance, and prosperity. There is no single solution to reversing fertility decline, but housing affordability is the first and most crucial step. Removing this key barrier will not only allow more Australians to start families but also lay the foundation for broader economic and social reforms that secure long-term population growth and national well-being.

As fertility rates decline in expensive metropolitan areas but stabilise in more affordable regions, it is evident that housing affordability and accessibility must be at the heart of any strategy to support family formation and sustainable population growth. Research consistently demonstrates that fertility rates are closely tied to economic conditions, particularly housing costs. If this fundamental issue remains unaddressed, Australia risks deepening its fertility crisis and jeopardising long-term social and economic stability.

Australia is not alone in facing this demographic challenge. Other nations have successfully implemented policies to reverse fertility decline, offering valuable lessons. While Australia’s policy landscape differs, there are clear lessons to be learned from Hungary’s approach, where integrated policies on housing, taxation, and family support have helped reverse fertility decline.

Improving affordability must be a top priority, balancing both supply and demand-side measures to ensure young Australians can afford homes suited for raising families. As Joel Kotkin notes, ‘Future success will favour cultures that uphold the family’s place, not necessarily as the exclusive social unit, but as a fundamental one that fosters societal cohesion and continuity.’

Housing policy is fertility policy. Getting it wrong will shape Australia’s demographic and economic future for generations. If Australia wants to reverse this trend, policymakers must prioritise housing affordability as a national priority. This means urgent reforms to land use planning, financial incentives for family housing, and policies that align homeownership with family formation. The longer we wait, the harder it will be to reverse the decline.