I stood at the Bar-Lev lookout with the battle-hardened Colonel of the Israeli Defense Force.* At a respectful distance, the IDF troops under his command fell back as we studied the Egyptian Border with Israel.

I listened closely as the Commander of The Paran Regional Brigade, a key unit in the IDF’s Southern Command, methodically explained border security with Israel’s Peace Treaty partner, Egypt.

Diagonally opposite our Israeli vantage, we looked across the North Sinai demarcated by the Israel-Egypt border. Below was an Egyptian military outpost against the backdrop of the immense Sinai desert.

- Photography by Sasha Gusov. Instagram @sashagusov

The Colonel pointed out the double fence – one distinctly older than the other. Within its perimeter was a newer, taller fence built several feet inside the Israeli border. It exists as a result of recent migrant flows and human trafficking from Sudan encroaching Sinai, forcing Israel to strengthen the border.

To my left and downhill sat a small shack with nothing but a tarpaulin stretched over it as a feeble cover against the blistering Egyptian sun. It was an outpost for a lone Egyptian soldier patrolling his station.

I was travelling (at my own expense) across Israel from the Syrian-Lebanese border to the Egyptian border for two weeks ahead of the October 7 anniversary. My intention was to learn from the IDF how Israel’s multi-front wars were unfolding and to bear witness to Israeli’s survivorship – not only of October 7, but of the intensely difficult year that had followed.

- Photography by Sasha Gusov. Instagram @sashagusov

My visit was also a personal one, allowing me to speak at Reichman University’s 24th annual Shabtai Shavit World Summit on Counter-Terrorism, put on by the university’s Institute of Counter-Terrorism.

Arriving in the early morning of October 2, hours after the onslaught of hundreds of Iranian ballistic missiles, I was keen to see as much as possible. Before departure, I contacted the IDF’s public diplomacy offices for broad access across the country.

It was almost exactly a year earlier that I travelled to Israel on my own initiative as a human rights observer to witness the aftermath of the Hamas attack and report on the testimony of Israelis. As an observant Muslim devoted to my faith, but vehemently opposed to Islamism – especially violent Islamist jihadism – Israel’s war on both Hamas and Hezbollah remains top of mind for me.

Through binoculars, I could see an Egyptian surveying the vast solitude of the afternoon Sinai, alone at his outpost.

‘He is looking in the right direction. The threats to Egypt come not from here but from the Sinai desert,’ the Colonel* said.

The Jewish Israeli Colonel* and his Muslim Israeli Captain* explained that the Sinai at night was rife with human smuggling as well as terrorist movements. This is particularly true since ISIS had been subdued in this region some years earlier. The Egyptian Armed Forces continue to wage persistent retaliatory campaigns to dismantle ISIS elements and contain them within the North Sinai.

- Photography by Sasha Gusov. Instagram @sashagusov

Almost due north, 40 miles from here, is Gaza. To the northwest, Rafah. On October 7, 2023, the Colonel* had rushed to respond to what was only later understood to be a massive invasion of Hamas operatives into Israel. Leaving a skeleton force in place, he mobilised the Paran Regional Brigade and went to war with Hamas.

At one of the furthest outposts of the Jewish State, I could imagine his lonely, rugged drive into battle past numerous world-renowned urban warfare training centres that the IDF has built to fight exactly such insurgency warfare. I had arrived by the same roads, passing these installations, pockmarked by live fire, on my way to the base.

Later in the afternoon as the heat intensified with the Captain and others in the Brigade, I walked down to the Nitzana crossing point with the Terminal Manager who showed me where humanitarian aid trucks from Malaysia and the Emirates had just been cleared and sent northwards by road along the Philadelphi Corridor to the distribution points inside Gaza.

Less than a week later I was in New York City when I heard that Yahya Sinwar, arch-terrorist and leader of Islamist jihadist terror group Hamas in Gaza, had been killed by the IDF.

- Photography by Sasha Gusov. Instagram @sashagusov

Sinwar would die an appropriately ignoble death on the same soil where he still held captive hundreds of hostages and on the same land where he held captive millions of Gazans to face Israel’s defensive war.

As news reached me, first through confidential channels and later in the wider media, the countless Israelis I had met since October 7 of last year flashed through my mind.

I also thought of the new glimpses I had been afforded on this recent visit this year. I thought not only of the Colonel commanding the Paran Brigade on the desolate Israel-Sinai Border, but also, at the Northern end of the Jewish State, of the young yet already seasoned Israeli Major of the 210th Division. This is the Bashan Division responsible for the Israel-Syrian border.

The Major* explained to me the evolving border tensions at the Quneitra Lookout Point. I now understood how Islamist Iran cultivated allegiance, through revivalist Shia Islamism, organised crime and exploited Assad’s political vacuums at Syria’s margins. Out of our sight, Russian patrols coursed the Syrian lowlands. These vacuums will continue to threaten both Israel and Syria

As Sinwar’s death made global headlines, I thought of the female IDF commander*, a survivor of the brutal Hamas attack on IDF military base Nahal Oz. On this recent trip, a year later, she detailed her harrowing experience, including ordering her own execution by her subordinates in the event of being kidnapped and tortured.

Miraculously she survived grenade attacks and gunfire, though witnessing genocidal violence, sexual violation, and degradation which befell dozens of IDF female officers murdered or kidnapped that day.

As a physician, I examined the scars on her palm. To her, they formed the shape of an ‘A minus’. To me, they were a newly-forged stigmata.

- Photography by Sasha Gusov. Instagram @sashagusov

Leaving the commander, I walked, with the IDF liaison officer to elsewhere on the base and into the Nahal Oz ‘Hamal’ (Hebrew, the War Room) communications and command centre. It was now a burned-out husk of its operational days; torched by Hamas while unarmed female soldiers burned to death inside.

A year earlier, I had been in the morgues at Abu Kabir in Tel Aviv Yaffo, chaired by Dr Chen Kugel as Dr Michal Peer explained the inferno caused by the thermobaric grenades had left only crystal remnants of the human teeth and vertebrae that we held in our gloved hands.

We had studied the architectural blueprints of the same burned-out command centre I was now walking through, trying to tie human remains to once vibrant women.

The year had come full circle as I saw where these women soldiers had died in a furnace of flames.

But the Israeli life force is indomitable.

In downtown Tel Aviv during this visit, I lifted my head to the sound of BlackHawk rotors as the helicopter came into land, less than 15 minutes after airlifting wounded IDF soldiers to the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (affectionately known as the Ichilov) extracted from the battlefield to the waiting choppers at the Gaza beach.

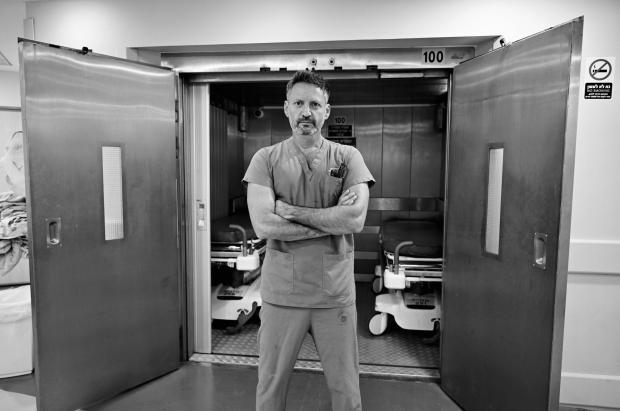

More than a dozen stories are overhead on the helipad. Dr Eyal HaShavia**, Chief of Trauma Surgery in scrubs and clogs, stood ready to whisk the wounded down to the trauma bay. After a year of this routine, the team has perfected the transfers in under two minutes and 40 seconds.

Ahead there are hours of complex surgeries with multiple teams operating in concert, sometimes as HaShavia holds ruptured great vessels in his fist while conducting an orchestral response of modern medicine.

I learned that as Sinwar’s body was identified by soldiers, HaShavia and his team worked to heal more soldiers, this time from Lebanon. It is a testament to team effort that the CEO of the Ichilov, Professor Eli Sprecher, stands with HaShavia in the trauma bay ensuring the trauma team has everything they need.

HaShavia has operated on more than 250 critically injured soldiers since Sinwar launched the war one year ago; many choosing to return to combat. Like the IDF this long difficult year, under intense pressure, HaShavia stands his ground, so much so that his tall, rangy silhouette is practically part of the Tel Aviv skyline – the H on the helipad stands perhaps more for HaShavia than even the helicopters.

South from here, back towards the Egyptian border and Israel’s hinterlands, the shy female commander* shows me how to first enter and then command the Merkava 4 tank. I crawl on my hands and knees into the belly of the machine, and eventually stand up in the turret and clamber out to stand on the beast and take in the view. I thought how it was only a few years ago that I had first stooped deep into a Hamas tunnel not far from here in the Gaza envelop, oblivious to where the wars would take each of us.

In the past year, many knew Israel sought not vengeance but justice. A year has felt like an aeon; yet when the day arrived, the moment was right.

Sinwar’s death is a testament not only to human justice but to God’s – a victory of good overcoming evil. Sinwar was executed for committing innumerable crimes against humanity and even more so, a heinous crime against God.

Islam has a special language and contempt for such monsters the Qu’ran (95:5) speaks of them as the ‘أَسْفَلَ سَٰفِلِينَ ‘Asfalas Safleen’ in a verse stating:

‘Then, if he works iniquity, we reject him as the lowest of the low.’

Found above ground, without a phalanx of hostages and bodyguards, with almost no one left to trust and a wristwatch to coordinate times, Sinwar likely awaited an operational maneuver, perhaps moving to a new subterranean lair – or maybe engineering his own extraction.

Holding siege in his last moments with a cane to a drone, Sinwar would die by the hands of soldiers of the same Gaza Division that once so agonisingly failed on October 7, 2023.

As a legendary Bedouin Unit 585 Commander* wrote to me via text message, the infantry School Brigade 828 would finally ‘close the circle and close the account’.

With Sinwar eliminated, the work of liberating the 101 hostages can now move ahead full force and the days to an end to the war of Hamas on Israel are hopefully coming to a close.

Israel is finally ascendant.

*(for security purposes, IDF officers are not named)

** Name released with permission

Dr. Qanta A. Ahmed, Senior Fellow, Physician, Senior Fellow Independent Women’s Forum; Life Member, Council on Foreign Relations.

All photos are supplied with permission by Sasha Gusov whose most excellent work can be found here and at their Instagram @sashagusov

Sasha Gusov is a Russian-born, UK-based renowned photographer known for his distinctive and insightful approach to capturing the human comedy of manners. His work has garnered international acclaim, featured in the British Journal of Photography, and has led him to work with prestigious clients including Vogue and the English National Ballet.