It doesn’t take a university degree in education to recognise a connection between a dismal classroom environment and poor academic results, with the most recent OECD Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) confirming Australia is seriously deficient in both.

The most recent PISA results reveal, incredibly, half our pupils failed to reach proficiency standards in maths and 43 per cent failed to reach proficiency in reading. Our students are now four years behind ladder-leaders Singapore in maths, and more than two years behind them in reading and science. At the same time, PISA also found the nation’s classrooms are among the most disruptive in the world, ranking 71st out of 81. More than 40 per cent of students confirmed there is ‘noise and disorder’ in their mathematics classes all or most of the time. Almost a third said the teacher had to wait a long time for students to settle, with one in five students saying this occurred in most classes.

In addition, school principals have been subjected to levels of physical violence, threats, and bullying never before seen in the history of a long-running national survey measuring wellbeing among school leaders. Of the 2,300 principals who took part in the Australian Catholic University’s annual principal safety survey, 48 per cent reported experiencing or witnessing physical violence, and about 54 per cent were threatened with violence.

Amid this measurable mayhem, what warrants close attention are the ‘student-centric’ teaching practices, long understood to be detrimental, which persist in many of our schools.

In recent decades the Australian education system has been dominated by a ‘student-led’ educational philosophy, where the teacher is seen not as the authority figure and responsible adult, but as a guide or partner in a child’s education – a friendly sidekick in the learning process and an all-embracing carer, sharing the student’s journey. This feel-good educational ideology is readily identified by a classroom where students – often with their backs to the teacher – are seated at tables bunched in groups, providing almost unlimited opportunity for distraction.

Discipline in such environments is viewed more as a counselling session. Misbehaviour is addressed with ‘round table restorative practices’, involving discussion of how one ‘feels’ about the situation, which the teacher must then document. When a student misbehaves, the underlying message is that the teacher has somehow failed to understand the student or failed to cater to their specific learning needs – and more teacher attention is required. It could be the lesson should have been more engaging because, naturally, a bored student will ‘act out’. Regardless, the ‘student-led’ education philosophy, by design or unintended consequence, lays the blame for an individual student’s poor behaviour largely at the feet of the teacher. Quick and at-the-ready punitive consequences for poor behaviour have more or less been removed from the teacher’s toolkit – viewed as old-fashioned, negative and inappropriate. The burden to ‘try harder’ to address student misbehaviour falls on the teacher – not the misbehaving student.

Students and parents today are demanding more of teachers than 20 years ago, and results have only gone backwards. At its core, the problem is the current and widely employed classroom practices which actively undermine teacher authority and morale, and adversely impact the teacher’s ability to deliver productive lessons of the highest possible quality.

Explicit teaching of phonics was demonised and, starting in the 1970s, was replaced with ‘student-led inquiry-based learning’ which relies heavily on strategies to guess words based on pictures and context. In a recent announcement, Victoria’s Education Minister Ben Carroll said, from next year, all government schools would employ the explicit teaching of phonics for a minimum of 25 minutes a day. Unsurprisingly, the mandate was instantly rejected by the Australian Education Union as evidence of the Minister displaying ‘breathtaking disregard for teachers’ and advised its members to ignore the announcement.

Teacher unions continually demand more funding, claiming this will address the decline in standards, and that the student-teacher ratio be reduced. However, experience demonstrates that more funding will not address the crisis in our classrooms. In Victoria, Institute of Public Affairs’ research shows while the state’s education budget increased by 30 per cent (from $10.73 billion in the 2013/14 financial year to $14.13 billion in the 2020/21 financial year), there was barely any improvement in student performance. Victorian NAPLAN scores in reading and numeracy today have improved less than 1 per cent since 2015. Excuses that the pernicious effect of social media is to blame ring hollow because all children in the developed world have access to social media.

The number one ranking in PISA scores is Singapore, where well behaved and respectful students respond to the encouragement of suitably trained and supported teachers, producing academic outcomes that put Australia to shame. There are, of course, important cultural and historical limitations to comparing Australian schooling with that of Singapore, and not all of their classroom practices should or could be adopted here. However, key to Singapore’s success is the notion that teaching is an honourable profession and that teachers will stay fast to the highest standards and ideals of their profession. Consequently, teachers are held in high esteem and students are taught and expected to demonstrate respect. Disciplinary consequences such as detention, suspension, and corrective community service are mainstream.

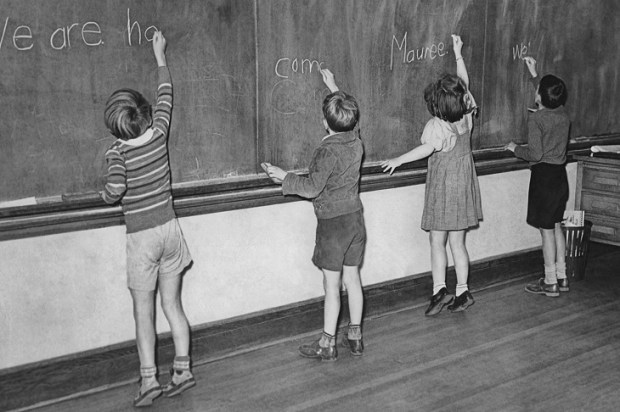

Another ‘old-fashioned’ educational model is England’s Michaela School, often referred to as the ‘strictest school in the UK’. At Michaela, students work in an atmosphere of sober scholarship. ‘Demerits’ are handed out for the slightest errors – forgetting a pen for example. Two demerits in one class result in an automatic detention. Every detail of the school environment is designed to maximise the amount of learning time. Unlike many Australian classrooms, Michaela students are expected to sit bolt upright, face turned to the front. Students are taught and expected to ‘track’ the teacher with their eyes to maximise concentration and minimise distraction. The emphasis is on the teacher and, importantly, there is no enquiry learning or group projects.

Michaela employs strict and explicit teaching methods that have seen a French class observed and described as indistinguishable from the level you might expect at an elite school such as Eton. But Michaela School is not an elite school, it is a community school with its pupils among the least privileged in London. Five years after first opening its doors to pupils, Michaela’s results placed it as one of the best non-selective schools in the country. In the GSE exams, more than half (54 per cent) of the students gained the equivalent to the old-style ‘A’ in at least five subjects, which was more than twice the national average of 22 per cent. 18 per cent of Michaela students achieved an overall grade 9 status, the highest grade, compared to 4.5 per cent nationwide.

Fifty-six schools in New South Wales have overhauled the way they teach, shunning student-led learning in favour of a direct, traditional instruction style. In many cases, new furniture was purchased so students could be seated in rows facing the teacher. Results at one school, where a quarter of students come from a disadvantaged background, showed 94 per cent of year 5 students achieved the top four bands for reading in the 2022 NAPLAN tests, compared to just 69 per cent in 2017.

Marsden Road Public School in NSW adopted similar practices, abandoning fashionable teaching practices, and has transformed its results, with students recently achieving above the state average progress in reading and literacy. At the beginning of each year, all Marsden students do a two-week crash course in basic skills such as learning to walk between classes quietly, in neat double lines, and to greet teachers politely.

For too long Australia’s fundamental education policy settings have been notable for fads which, rather than being abandoned when proven unsuccessful, have remained in place. As a result, we have an education system set up to fail teachers and students alike.

Amplifying the inherent flaws of student-led learning has been the introduction of the National Curriculum, mandatory for every student in Australia. This has dramatically shifted learning from a system based on knowledge and facts, to one underpinned by political ideology.

The problems facing our teachers are compounded by the substandard training they receive at our universities, which is having a detrimental impact on the career prospects of our teachers, setting them up for failure. IPA research found that universities are churning out teachers who spend as little as 10 weeks in a four-year degree learning the skills to teach core subjects, such as reading, writing, mathematics, history and science to students. When this shortcoming is added to the failure of student-led learning, it is little wonder discipline in the classroom is in freefall.

Learning to read, write and be able to compute mathematics is not a naturally occurring process. Students need to be explicitly taught. While there is a deep-rooted perception that explicit instruction is antiquated, cognitive psychology vindicates the timeless effectiveness of the approach. This method of teaching is also known to improve student behaviour, which in turn improves results.

Every Australian has a vested interest in seeing our students succeed. It’s time the adults in the room took back control.

Colleen Harkin is a former teacher and manager of the Institute of Public Affairs’ Class Action program.