Recently, a small miniature company in the UK, Games Workshop, announced a change to its longstanding lore. I won’t get into the details; it is enough to say that this went along the usual lines of enhancing diversity, inclusion, and equity, at the expense of the qualities that had made that fictional universe popular to begin with.

The result was a blowup of catastrophic proportions that damaged the company’s stock price and resulted in some very half-hearted social media explanations.

I grew up painting toy soldiers, so I felt a slight sense of irritation that another fictional universe – fictional universes being where we often say profound things about our inhabited non-fictional universe – risks becoming formless paste suitable for ‘modern audiences’.

Popular culture has become a proxy for the genuine wars about our actual culture, or what remains of it.

There are many terminally online types for whom Being is hinged on an IP dreamt up in a boardroom. These people, predominantly Millennials and Zoomers, are fanatical fans of their respective universe. There is nothing, in and of itself, wrong with this, provided there is some balance in one’s life. Rather, the problem is that Adorno was right, as much as it pains me to say it.

Popular culture, or what he called mass culture, has obliterated organic folk culture and aristocratic high culture, replacing it with manufactured market-based slop. It has further become a tool for social engineering in malfeasant hands.

Most great works of art are the products of a single mind, with a single intention, often not well-understood by the creator of that art. They act as a conduit for deeper truths about the world that we instinctively understand to be true, something native to all great art.

The collision between the single-mind and the marketeers is represented well in Star Wars. It began as the not-particularly-original imagining of a man with a decidedly teenage view of the world, successful in part because it rode a confluence of genres and a particular time, not unlike JK Rowling’s Harry Potter 20 years later. It successfully tapped the zeitgeist of the moment. Studios and publishers have tried the same trick ever since, and where they cannot determine the zeitgeist, they try to create it instead.The quality of these products – as we must regard them – was insignificant compared to their market appeal. I loved Star Wars growing up, but left childish things behind, so the recent sequels left me cold, even without the myriad of disasters introduced by a progressive marketing crowd on a mission to create a new zeitgeist. Increasingly other Millennials have not left childish things behind.

This isn’t to say all popular culture is bad, but that it remains popular not in terms of having popularity, but in the old-fashioned sense of the word: that it is designed to appeal to the largest possible demographic. Its motivation is market forces.

Homer’s Iliad was not motivated by market forces. Goethe, Shakespeare, and whoever else among the greats you’d like to list were not motivated by market forces either. Their popularity was incidental, a comment on their quality.

Modern popular culture puts the cart before the horse, aiming for popularity without quality, rather than quality without popularity. Too often both are sacrificed. But the fact that we receive a poor product, evidenced by a cursory look at any streaming services’ offers, is only the beginning of our problems. The deeper problem is two-fold; in what popular culture has become, and in what it aims to do. Both are prospective tragedies for the human spirit.

To understand the vast appeal of popular culture in today’s world is not merely to comment on the growth of entertainment technology, disposable income, and leisure time. These are all important factors, so obvious they need no further stating: factors that have allowed ‘real life to become indistinguishable from the movies’, as Adorno put it. They have made popular culture the increasingly monolithic force it is today, where nobody can avoid its touch. It is hard to imagine Edward Said giving Frank Herbert’s Dune the time of day, despite its obvious orientalist themes, half a century ago. They let the man cook.

Ancillary to this, and seemingly unrelated, has been the collapse of organic communities, identities formed by a fistful of soil, and the mutual usefulness of these communities. In industrial society, we saw this begin, though communication and transport had not become sufficiently advanced that individuals could escape the proximate, whether Five Points in New York or Manchester in England or whatever metropolis was thrown up to accommodate the workers who flooded in from the countryside. Post-industrial society completed the process by removing the individual from neighbourhood, creche, and family. We spread now wherever we please, but have found that freedom is illusionary and loneliness is not. Many of the ills of post-modern society can be laid here, though we are far from articulating an answer to this problem, if we even collectively regard it as such.

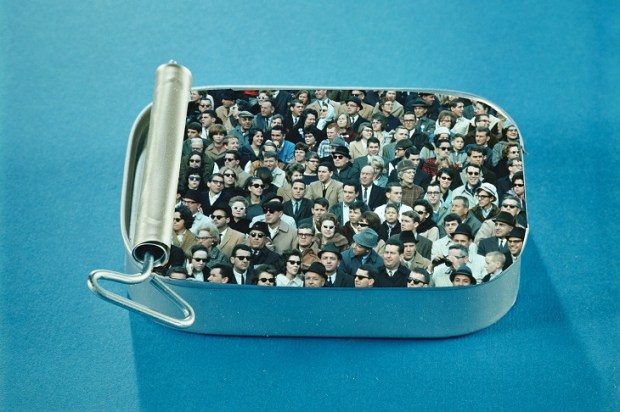

Another seemingly unrelated tragedy of post-industrial society is the collapse of usefulness. Many are not useful to the places we work, which in turn are of little use themselves beyond a paycheck. The secret cry of many a human heart is not merely to be known, and know in return, but to be valued. Value is not like fiat currency; we cannot print it at will. To be valued you must do valuable things, but the scope for this, as the iron cage of bureaucracy and the law of degrees of separation holds court, is increasingly diminished. Nobody is invaluable, we are reminded; they will advertise your position before you are cold in the ground. We might live in great cities heaving with human life, but much of it is interchangeable, like a nest of ants. Our souls yearn for small communities where, like in Cheers, everybody knows your name.

Of course you can go to Cheers every day, but you can equally not. You can participate in social sports, or stop showing up after the first game. You can attend church, but you are free not to, if something about it is unpalatable. This, to the liberal mind, is freedom, because the modern liberal mind believes duty to anything other than oneself to be the worst kind of treason. But non-voluntary communities are where human beings find their place, and we have precious few of them left. Prisoners who long to return to their cells and soldiers unable to adapt to civilian life are unknown to themselves shorn from communal bonds, even bonds as reduced and callous as those found within a correctional facility.

Into the void of community, family, and the ‘viscous historical paste’ of blood, has arrived simulated marketed fantasy to fill the void, in fandoms and fanatical Reddit posts and hordes of commentators on every corner of the internet. Simulated value, gained by adherence to simulated universes, pleases what we must concede are ultimately simulated people. Those Millennials for whom, as Dave Greene said, ‘found adulthood to be a disappointment’ have retreated into childlike fantasy instead. They are self-actualising into an a priori consumer product. A society that knows more about the lore of the Elder Scrolls than its own history cannot boast of a bright future.

The obvious answer to all this is family life, but here we find the ground salted. The sexual revolution did not create good people; it created people in search of happiness, an avenue ruthlessly exploited by a ruling merchant class without noblesse oblige. The right to happiness, however one conceives it, is the cornerstone of the post-modern liberal weltanschauung. Too often we find ourselves trying to build castles on sand dunes. CS Lewis put it well in We Have No Right to Happiness:

‘Secondly, though the “right to happiness” is chiefly claimed for the sexual impulse, it seems to be impossible that the matter should stay there. The fatal principle, once allowed in that department, must sooner or later seep through our whole lives. We thus advance toward a state of society in which not only each man but every impulse in each man claims carte blanche. And then, though our technological skill may help us survive a little longer, our civilisation will have died at heart, and will—one dare not even add “unfortunately” – be swept away.’

The difficulties of today’s life, where one feels as though something monstrous is about to turn the corner, have lost their traditional remedies. These remedies are genuine selfless and reciprocal bonds with others, and a propensity to look upward rather than downward. Any attempt by popular culture to fill this void – with its variegated fandoms and obsessive corners of voluntary community – is laughable. Attempts to do so are motivated by top-down grotesque corporate behaviour on the one hand, or the advancement of a certain set of principles by zealots on the other.

Thus the first danger presented by popular culture is that it has become a surrogate for genuinely lived life for vast swathes of post-industrial deracinated and deculturated Western populations, seeking reprieve from the harshness of a materially plentiful but unsatisfying manner of life. The simulacrum of the online world is analogous to the danger of the lotus eaters encountered by Odysseus. Such bugmen sacrifice themselves to live in fantasy forever.

The other danger of popular culture is the tool it is set on becoming, in the hands of a zealous few who view it as a means of moulding minds on a vast scale. The capture of popular culture, to the true believers on the other side, is at least as important as the capture of educational institutions was to a prior generation of leftists. This is evidenced by the fact they are willing to virtually bankrupt themselves to do it, which is not the behaviour of purely rational economic actors interested only in profit. They talk a lot about ‘reaching new audiences’, but I am no longer convinced. It seems more apt that they are trying to conquer existing audiences, and fold them into a certain worldview by the psychological equivalent of blunt force trauma.

You can see this in what Amazon did to Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, what Netflix did to The Witcher, and what is currently happening within Games Workshop. Video games, infested by parasitic studio entities, have increasingly veered in the same direction. This direction is the promotion of reductionist, unnatural, and obviously false representations of human life. Because it does not reflect truth, none of it can ever be art. It serves several purposes: a humiliation ritual – particularly for men who grew up with stories of the heroic masculine – a fulcrum encouraging unrestrained girl-boss feminism and a monadic view of gender, and a desire to demoralise and demonise European history and consequently our civilisation.

In sum, it promotes a postmodern, antihuman view of life, encased in suffocatingly shallow present political shibboleths that reflect their authorship: picked purple-haired young women writing in boardrooms with all the nous and skill of ChatGPT.

We might raise our hands and shrug; it is, after all, mere entertainment.

But this sort of thing constitutes the prime ideational output of our increasingly centralised and monochrome culture, and what it has become instead is a front in our culture war.

We can take from this the lesson the Melians did not take from the Athenians in Thucydides’ The Peloponnesian War: that the more seemingly insignificant the enemy, the more important the conquest. It demonstrates that nothing can be allowed to stand in the way of ideational victory for the other side, even in areas of life once considered trivial and frivolous.

When so many are addicted to media-consumption-as-life, and stake their very identity on its variances and show no desire to wean themselves from it, a great harvest of souls might be reaped.