Europe is in the midst of a series of conflagrations. Last Thursday, Dublin was set ablaze in response to a stabbing attack allegedly carried out by a man of Algerian origin on two adults and three children. A few days prior, a more metaphorical fire arose in Holland as long-time anti-Islam campaigner and ‘hard-right’ figure Geert Wilders emerged victorious in the Dutch election.

Australia, too, has had its own upheavals. Precipitated by the October 7 attack in Israel, we’ve witnessed calls to ‘gas the Jews’ outside the Opera House. We’ve even had cross-city convoys engaging in inter-ethnic violence.

This is only a partial list of our troubles though. The centres of our two biggest cities have been shut down for pro-Palestine protests for seven weekends straight. Jewish Australians no longer feel safe walking around their own cities. Children have been encouraged by the state to skip school.

These are only the latest threads in our long-fraying social fabric. Melbourne, for example, has returned to the gangland atmosphere of earlier this century with a spate of arson attacks on stores and shootings. Trust in government and institutions are at record lows. We even had BLM mobs storm through our cities a few years ago. Australia, as many are noting, ‘has never been like this’.

In spite of all this, there appears to be no appetite by the political class for any real reform. No matter how bad things get, the foundations of our political settlement seem unshakeable.

This settlement, of course, is essentially the End of History stance of Francis Fukuyama. It’s one of immigration-fuelled economic growth and socio-economic liberalism. It’s one which wants women in work and kids in childcare. It’s one of gambling, drug use, and alcohol consumption. In essence, it’s a continuation of an already unencumbered and multicultural market.

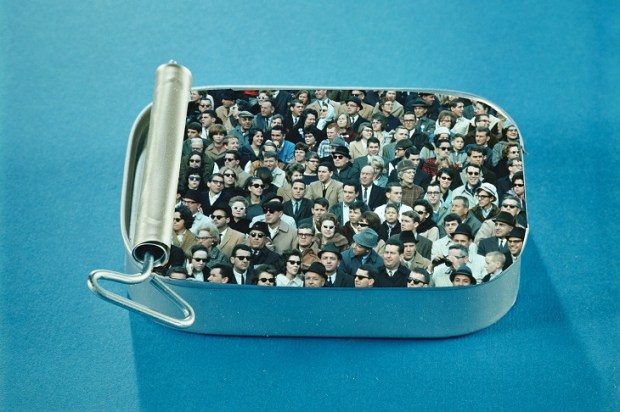

What we have, then, is what American historian Christopher Lasch referred to as a Revolt of The Elites. Punning on Spanish philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset’s Revolt of the Masses, Lasch described a cosmopolitan elite that had wilfully lost touch with the people it governed.

Per Lasch, our upper classes were ‘in revolt’ against the lower classes of their own countries. The working class was seen as ‘technologically backward, politically reactionary, [and] repressive in its sexual morality’. The Average Joe was ‘middlebrow in [his] tastes … complacent, dull and dowdy’.

The elites, however, were globalist in outlook and in possession of an ostensible superiority. Theirs was a ‘tourist’s view of the world’, one which was ‘at home only in transit, en route to a high-level conference, [or] to the grand opening of a new franchise’.

Our pursuit of diversity thus suits them to a tee. They’re thrilled with a life that evokes a ‘global bazaar in which exotic cuisines … dress [and] exotic tribal customs can be savoured indiscriminately, with no questions asked and no commitments required’.

This has obviously been the dominant ethos of the last few decades and it’s only accelerated since Lasch penned his work in the 1990s. Yet what has worsened since Lasch’s day is an elite insistence that their project continues. Echoing Thatcher, they assert that There Is No Alternative to their top-down program of mass immigration and uber-liberalism.

This is a stance we could call The Conceit of the Elites. As no matter how many demonstrable failings this produces – from the latest riots, to our feeble fertility rate, to our drastic education decline – they’re unwilling to alter their settings.

Yet as events in Europe have proved, this consensus is fraying upon repeated contact with reality. Western populations are increasingly unwilling to accept the direction in which their states are headed. They’re tiring of incessant demographic change and the violence it inevitably brings.

This is witnessed in the rise of Wilders and other parties of the right. Yet it’s also been embodied popular figures who, for example, have criticised the Irish establishment for their inability to protect the Irish people and threatened to take action themselves.

This is essentially what English writer Aris Roussinos has observed of the West as well. Roussinos’ warning that Britain’s centre-right Tory party will soon find itself outflanked by parties to its right as it has failed in its duty of providing genuine conservative governance.

As Roussinos notes:

‘The current order is a fragile interregnum: through this government’s failure to pursue moderate conservative policies, British Right-wing politics looks fated to move beyond mere conservatism.’

This appears to be the position of our own LNP too. If they’re unable to offer a credible conservative alternative to the ALP, they’ll surely be supplanted by someone who will.