The International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005, which finds its roots in the International Sanitary Conference 1851, is a legal instrument ratified by 196 member countries of the World Health Organisation (WHO), endeavours to: ‘Prevent, protect against, control, and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease.’ While its main objective is laudable – concerns arise about the potential erosion of human rights, dignity, and freedoms in its execution – this article provides a critique of these concerns, focusing on its ability to potentially censor information, which can negatively impact the fundamental principles of transparency, accountability, and inclusivity. By no means does this critique purport to be a conclusive and/or exhaustive discourse on the ideological underpinning socially constructing a perpetual state of global emergency, but it does represent the threat to human rights, dignity, and access to timely healthcare without the intervention of non-elected international bureaucrats with little to no accountability of the host nations.

IHR 2005 proposes to grant significant powers to WHO, that could, depending on which version is implemented, allow the institution to take drastic measures to control public health emergencies of international concern (PHEIC). It would have to be ratified by government. If it proceeds, these measures may include restrictions on travel and trade, monitoring individuals, or enforcing quarantines. Such actions, though intended for public health protection, may inadvertently impinge on the human rights of individuals and communities. At first blush, one may indeed be captivated by the emotional spell of idealistic government/state-controlled healthcare, as we had seen during Covid. But more striking was the lack of protections afforded to citizens by those institutions such as the human/civil rights lobbies, selecting instead to follow the Government line. It is not our intention here to reflect on anything more than the failure of institutions to protect the fundamental rights of citizens all over the world.

Mistakes that permitted unelected health bureaucrats to wave their emergency powers infringing fundamental human rights such as:

- freedom to earn a living;

- freedom of movement;

- freedom of association;

- freedom to participate in society;

- freedom to get married;

- freedom of religion;

- freedom of education, and so on.

These ‘mistakes’ went on for a considerable length of time – three years, in fact. Although the draconian measures are being slammed by some courageous lawyers, the medical fraternity, some media personalities, members of the community, emergency service workers, and former political leaders, the key institutions, and non-elected bureaucrats appear to be pursuing a monomaniacal extension of what we know is a controversial policy far exceeding policies experienced during the second world war in Australia.

Although some commentators suggest Covid is largely over, this cannot be further from the truth as many emergency service workers, airline employees, local council employees, and healthcare workers still face draconian occupational health and safety policies if they do not ‘choose’ to get a vaccine that has demonstrably failed to meet the highly publicised endpoints. Yes it’s time they admit failure. But now we face an even greater danger than the pandemic itself – a global threat under the guise of international collaboration and efficient sharing in future crises.

The proposed amendments to the IHR raise serious questions with regards to state sovereignty and the future of governance. They also encourage the stifling of dissent from the official line and wider panopticon-styled surveillance via a range of (digital) certificates, CCTV, facial recognition, digital currency, online monitoring, and censorship, controversies that were all accepted by, civil liberties and human rights organisations, traditionally the gatekeepers and protectors of human and civil rights.

Thousands of legal challenges all over the world, have been unsuccessful, but the lockstep approach appears to dovetail into the very concerns we are raising in this article, that is, no accountability at any level.

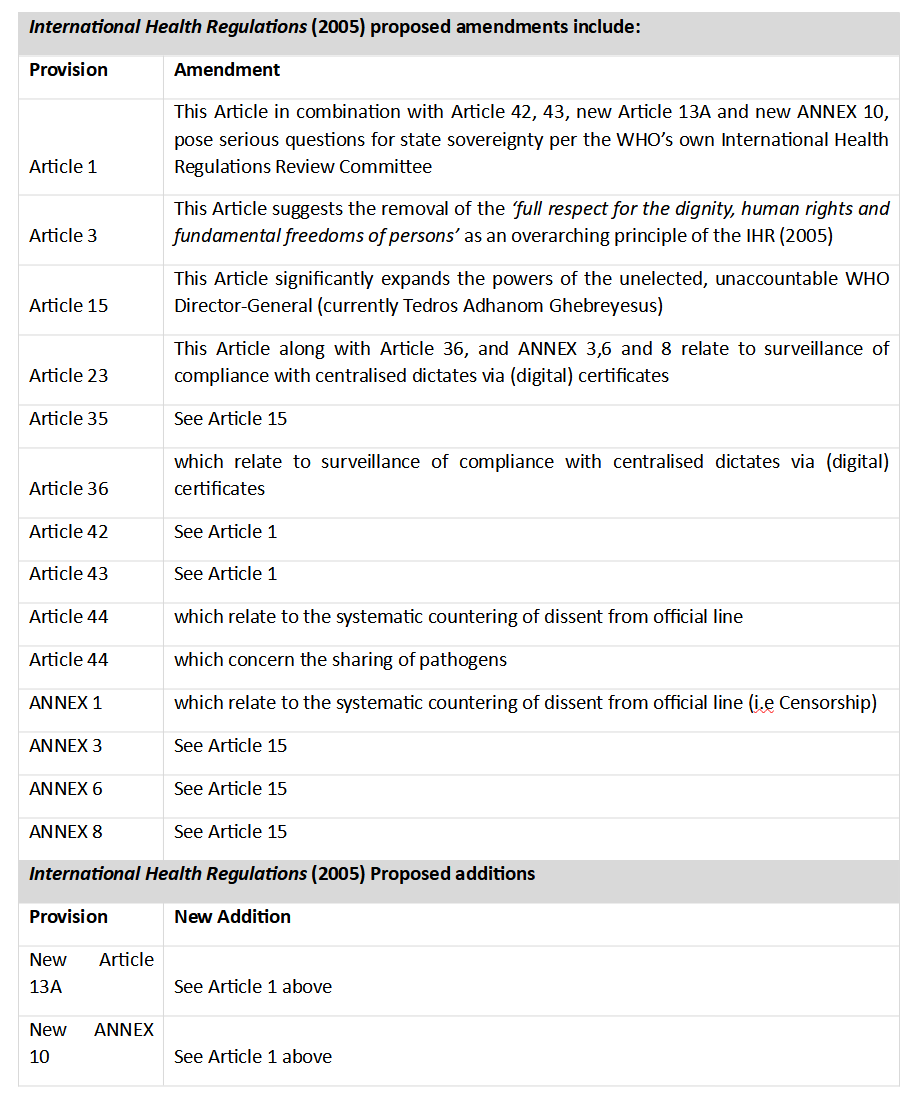

The proposals of greatest concern are included (but not limited) in the table below:

Further, the IHR must be viewed in conjunction with the WHO pandemic treaty.

The WHO Pandemic Treaty/Accord Zero Draft is a separate and complementary legally binding treaty which, if adopted, would:

- Cede undue authority over global public health to the WHO;

- Create a new cost-intensive, undemocratic supranational bureaucracy;

- Impose an ideological framework called ‘One Health’ for matters of global health, including support for gain-of-function research with pandemic potential pathogens (Article 9.8) and also encouraging a globally coordinated effort to counter public dissent (Article 17);

- Create ‘platforms that promote findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable data [on hazardous pathogens] available to all Parties’ – which would include dictatorships and state sponsors of terrorism, raising security concerns.

The IHR in effect overrides a country’s domestic law (after being ratified), and whilst those pushing for the amendments may attempt to persuade otherwise, it is unlikely to be a point of discussion if passed (ergo Covid era 2.0) ignorance and control will permeate without equitable or objective recourse. This means that if the Australian government agrees to the amendments being put forward by the WHO, Australians, and other nations could be under the control of the WHO director-general during health emergencies. Thus, any legal challenges run the risk of acceding authority to international entities prompting further consideration of Australia’s obligation to its own Constitutional protections.

As many may recall, NSW, Australia was never under a State of emergency, but yet locked down, introduced harsh measures, prevented citizens accessing timely healthcare, women denied access to mammograms, children denied access to education, small and medium business were devastated, and people unable to see doctors in person if they were not vaccinated.

The resulting juxtaposition means that if the WHO Director-General under global emergency powers orders vaccine mandates, shut-downs, digital passports etc., the Australian government would be compelled to comply, as we seen with former Prime Minister Scott Morrison closing down borders and issuing quasi-mandates for all federal workers.

But as we know, a choice involves a person choosing whether they want to eat a hamburger or salad, not ‘you will become a participant in a global clinical trial and if you do not agree, you will lose your job, cannot leave your home, travel internationally, you will be stigmatised, discriminated against and ridiculed publicly for making that choice’. Let’s face it, this was not a choice, this was straight out of the playbook of oppressive dictatorships where those who did not agree were purged from institutions such as state and federal police, paramedics, nurses, firefighters, and others. For example, the police were fired for misconduct, usually a charge reserved for corruption and serious wrongdoing, not because a person ‘chose’ to exercise their right to bodily autonomy. We knew then, as we know now, the Covid virus was never as deadly as claimed and whilst people did sadly succumb to this variation of the flu, people died with, not died because of Covid.

Firstly, let us examine the language of the IHR 2005 as it seems to unduly emphasise state security over human security. While Article 3 explicitly requires respect for ‘dignity, human rights, and fundamental freedoms of persons’, the state-centred approach often creates a problematic trade-off between health security and individual rights. Imposing quarantines or travel restrictions, as we’ve seen during the Covid pandemic, can lead to social isolation, stigma, and violation of freedom of movement, thereby undermining human dignity and the right to access timely healthcare.

Secondly, the IHR 2005 overlooks the need for individual consent in many cases, a cornerstone of medical ethics, overlooked and ignored by medical associations, doctors and bureaucrats all purportedly acting in ‘lock-step’. Under emergency circumstances, there’s a risk that people may be subjected to medical examination, vaccination, or treatment without their informed consent, raising serious human rights and ethical concerns, again matters that were ignored during the Covid era.

Moreover, the regulations do not provide sufficient safeguards to ensure the right to privacy and protection of personal data, another critical human rights concern. Disease surveillance data collection, while essential in tackling disease spread, often entails processing sensitive personal data, potentially leading to privacy violations. The rules surrounding data collection, processing, and sharing under the IHR 2005 are not explicit enough to prevent possible misuse. All of these concerns were neglected by the human rights lobby and institutions traditionally duty bound to protect.

Concerning the potential to censor information, Article 11 of the IHR 2005 allows WHO to consider unofficial reports of public health risks. While this mechanism can facilitate early warning and rapid response, it raises concerns over the credibility and confidentiality of information. WHO’s discretion to manage and disclose information might inadvertently lead to the suppression or alteration of information.

Although widely touted by the pseudo pharmaceutical salespeople such as government ministers, media, sports stars, bureaucrats, institutions, and employers as meeting these endpoints and failing, the switch in narrative orchestrated by the former government has moved towards preventing ‘serious disease’.

Thus Article 11 may be an enabler of further self-aggrandising conduct where unofficial reports become the backbone of institutionalised science used to lockdown citizens. One may be forgiven to think this was a fable, but it is written in black and white, and everyone has lived this over the past three years. Whether you believe this or not is your decision.

The IHR 2005 lacks explicit provisions that protect whistle-blowers and health professionals who might provide the source of this unofficial information, particularly if the information is misleading or deceptive. This shortcoming undermines the principle of transparency and could create a chilling effect on free speech, restricting open discussions about public health emergencies and place governments and international bureaucracies as the dominant treatment provider of individual health.

In addition, the IHR 2005 does not adequately address the issue of equity. It underestimates the socio-economic impacts of health measures, which often disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, again, the same people who were ignored are now being asked to trust in a system that coerced their compliance under the semblance of a marketing campaign suggesting they had a ‘choice’. Policies should not further exacerbate existing inequalities, and emergency health measures should take into account the socio-economic context and ensure that the rights and needs of marginalised and vulnerable groups are met. IT is important to note, that the wording, harks back language commonly found in writings relating Marxism, communism, and socialism. ‘You will own nothing and be happy.’

The authority of WHO in declaring PHEIC, as stipulated in the IHR 2005, creates a centralised decision-making process, which could undermine the democratic principles of inclusivity and participation. It is essential to involve the affected communities and consider their perspectives in decision-making processes regarding public health emergencies.

In conclusion, while the IHR 2005 plays a crucial role in managing global health security, it raises serious concerns about the potential erosion of human rights, dignity, and freedoms. The authority to censor information could undermine transparency and free speech, while the regulations’ state-centred approach and lack of emphasis and direction points towards a totalitarian centralised control that can only be compared to a panopticon-styled state of perpetual surveillance and social control. Where the traditional institutions of power have otherwise abandoned the citizens and their rights, we must ask ourselves, when something goes wrong, you will need to complain to Caesar, about Caesar and hope that Caesar will take your side. I cannot answer this, but if the past three years can point towards an answer, we can only assume this endpoint will not be met.

‘We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is when men are afraid of the light.’ -Plato