In the wake of Australia’s latest customer data exfiltration attack affecting possibly 14 million Latitude stakeholders, we read that the rate of corporate cyber attacks advised to the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) is now in the realm of one report every seven minutes (though the true attack number is believed to be far greater).

Financial costs of cyber hacks range from an average of $40,000 impact on small businesses to an estimated total of $ 40 billion per year across the Australian economy. Thereafter, you have the inherent non-fiscal costs to bear including business downtime, brand damage, legal action, regulatory imposts, and ruptured stakeholder trust.

Yet while rental homes must have (in Victoria) smoke alarms fitted, there’s no requirements for businesses to have cyber protection processes in place or active policing of these systems.

With cyber incidents increasingly scaring the bejesus out of boardrooms the length and breadth of the nation – and compromising citizen data security – it’s perplexing no politicians or political parties are insisting on mandated testing of cyber-crisis capabilities and processes, given the ubiquity of online data sharing and engagement in almost all our lives.

And as the federal government embraces its role as a Digital ID facilitator and custodian, concerns have been equally raised over its lack of mandated annual assessments and pentests (tests for system penetration vulnerability) to preclude and prevent issues and crises developing as government agencies morph into digital depositories!

Now when it comes to protecting property and people in my home state, Victoria’s local Residential Tenancy Regulations make it mandatory that landlords and premise operators undertake gas, electric, alarm, and amenity safety checks every two years for appliances in any rental property, and they insist that smoke alarms are tested annually to help combat the 3,000 home fires per annum occurring in Victoria (the national figure is around 15,000 house fires per year). Landlords in Victoria failing to comply with RTR, face fines and other penalties.

Victorian homeowners are advised (by the VBA) to check their own smoke detectors are in good working condition every month. The regular testing rationale is that having a tried and working alarm that flags danger early can negate the worst – most deadly – consequence of fires, i.e. death.

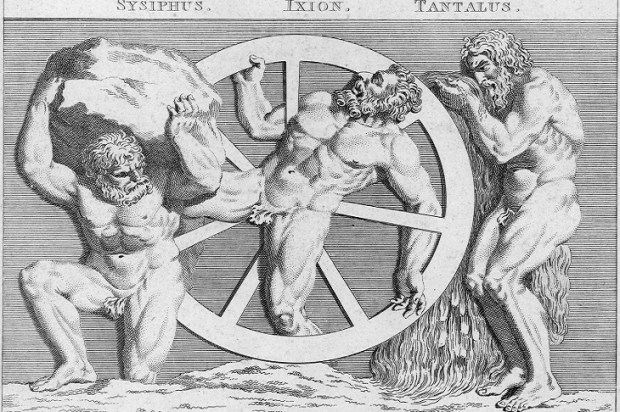

But it seems weird that such mandatory safety measures seem only to apply to these small items – smoke alarms, appliances, power cords – with relatively few moving parts. Where are the compulsory and enforced resilience requirements for government and corporate organisations – with multiple and complex moving parts – to conduct regular tests and remedial works on their cyber security plans and data safety processes? Sure there are suggested or recommended requirements, but few enforced digital decrees.

Missing, too, are the pre-emptive consequential and fiscal penalties for those organisations who play fast and loose with our data; material that we own yet temporarily loan to these corporate and governmental monoliths to store, use and protect.

Of course, we have the nation’s Security Legislation Amendment (Critical Infrastructure Protection) Act 2022. It outlines how any entity that has an IT system of national significance should report incidents quickly and must have a crisis incident response plan (section 30CD) and may have to do a cybersecurity exercise (section 30CM) but, again, it doesn’t mandate and enforce trialling, testing, and proving the efficacy and robustness of cyber handling and related crisis response capabilities. In this, Australia’s cyber-crisis readiness systems seem mostly self-policing.

Remember, too, the SLAA suggestions apply only to organisations whose business is of national significance. What about all the other corporations who store masses of our public data yet whose raison d’etre is entirely more transient or terminable? Worryingly, a June 2022 AICD study found only 53 per cent of company directors surveyed had any formal cybersecurity plans in place.

So they know they’re exposed but who’s forcing them to do the right thing regarding our personal info?

Corporations – and their directors – whose cyber risk management plans, processes, and controls are deemed inadequate, might face the risk of prosecution and fines under both the Corporations and Privacy Acts. But these consequences emerge after the damage has been done, rather than take pre-emptive steps to minimise or preclude possible damage to citizens’ digital property.

Various government agencies – incl ASIC and APRA – plus industry peak bodies, insurance companies, and consultants regularly offer advisories, guides, tools, and workbooks to help entities draw up and customise their crisis and emergency plans, but who’s checking that these plans get drafted, far less get tried, tested and tweaked to be absolutely fit-for-purpose?

Meanwhile, we regularly hear and read about organisations in crisis who claim to have been ambushed by unforeseeable threats and risks: their cybersecurity systems were unexpectedly breached; the executive and Board oversight was lax; certain fiduciary responsibilities were not adhered to; due political process appeared compromised; staff entitlements were not honoured … the shocking list of excuses betraying unpreparedness for crises goes on and on and on!

It’s a reality that cyber risks and data threats cannot be entirely eliminated, but they will increasingly impact the lives of many more Australians than, say, house fires ever will.

Mandating that smoke alarms are regularly checked and tested for full functionality is a great and widely accepted thing. Needing to have a functioning early warning and response system is essential so houses and premises don’t burn down leaving only rubble, ruination, and bitter regret.

With the culmination of cyber crises evidenced today, more must be done to compel or motivate governments, corporate companies, and social media monoliths – holding broad access to our digital data – to invest in and regularly and robustly test their cyber crisis procedures and security systems.

The alarm has been sounded; with around $40 billion of financial losses at stake, you’d think all digital enterprises might just have ample motivation to do a lot more to prevent and prepare for cyber risk and threat.

Gerry McCusker is the principal adviser at crisis simulation tool The Drill: www.thedrill.com.au