In one important way, the death of Pope Benedict last week was the death of reason in an increasingly secular world; even perhaps the death of reason in Christianity. Strangely, Benedict’s reason was not the result of his great faith. Rather, his reason was the result of his devotion to scholarship, a scholarship that traversed the writings of the great minds from the time of Socrates to the present.

To that must be added his knowledge of Scripture from a life-long study of the Old and New Testaments and the competing texts of Judaism and Islam. Benedict’s Christian faith was not a dogmatic adherence to an ancient doctrine, rather, it was based on a reasoned opinion formed over years of intense study and reflection while never denying the possibility of miracles in the face of claims by natural science, a possibility that can never be disproved by natural science.

The rule of reason was nowhere more evident than in Benedict’s 2006 Regensburg speech entitled Faith, Reason and the University, for it is only in the bounds of university – despite the views of university administrators, social scientists, and our Federal Court – where reason can flourish.

His speech dwelt on a dialogue carried on in the 14th century in Ankara by the Byzantine emperor Manuel II Palaeologus, whom Benedict describes as an educated Persian. While the purpose of the dialogue was to examine ‘the structures of faith contained in the Bible and in the Qur’an’, it dealt especially with the image of God and of man as found in the three ‘Laws’ or ‘rules of life’: the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Qur’an.

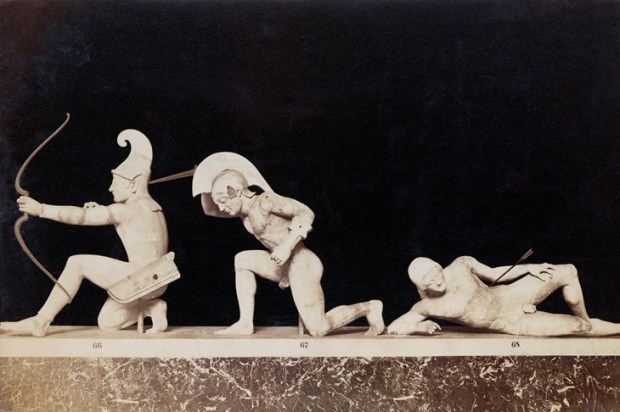

In the course of Pope Benedict’s speech, he repeated the rather harsh description that the Emperor Manuel had applied to the prophet Muhammad’s command ‘to spread by the sword the faith he preached’.

In a show of defiance, the Emperor had said that, ‘Violence is incompatible with the nature of God and the nature of the soul. God is not pleased by blood – and not acting reasonably (σὺν λόγω) is contrary to God’s nature.’ The God of reason was always held out as the God of peace.

Although the Emperor described the scheme to spread the faith by the sword as ‘evil and inhuman’, the Pope three times regretted the Emperor’s employment of such harsh terms.

Unfortunately, Benedict’s regret was not enough to spare him the violent and outrageous reaction of some Muslims who chanted ‘hang the Pope’ as they left the mosques in Kashmir after prayers. Others called for him to be replaced. Both examples vindicated the Emperor’s criticism of the direction that Islam had taken.

Benedict referred to the teachings of the 11th century Islamic philosopher, Ibn Hazm. ‘God is not bound even by his own word,’ Ibn Hazm concluded. This had the effect of assuming that Allah was not reasonable but could be capricious.

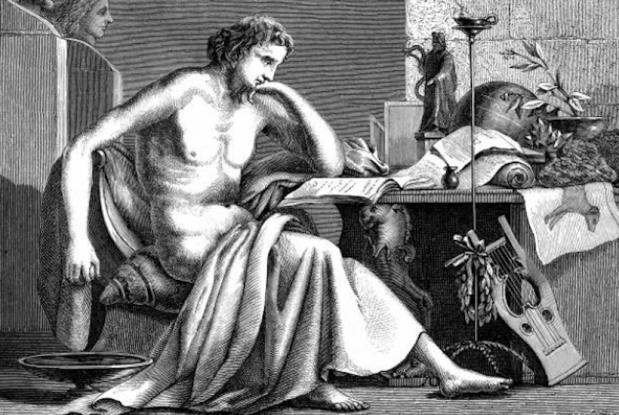

In contrast, however, the Christian view of God as witnessed by the Gospel of St John identifies God with reason: In the beginning was the word/reason (logos) and the word was with God and the word was God. Further, in the beginning, the God of the Hebrews created man, male and female, in his own image, and man is defined as the rational animal.

That question, whether God is the God of reason or unreason, had occupied the minds of religious scholars, Christian and Islamic alike, for hundreds of years.

The American scholar Robert Reilly tied the source of a God without reason in Islam to the attempt in the 7th and 8th centuries in all religions to reconcile God’s omniscience and His omnipotence. The Christian notion of God as reason became firmly set in Christianity and the God of Islam was not always unreason. The philosophical works of the Islamic Mu’tazilite school of rationalist philosophers demonstrates conclusively that Islam had been Hellenised by the works of Aristotle and that Allah was reason. How then did Islam’s understanding of Allah change?

The philosophy of the Mu’tazilites was essentially Aristotelian and Aristotle had proven that the God of nature was reason. As man was created with reason, the Mu’tazilites argued that statements in the Qur’an must be understood in accordance with reason which had the effect of denying the use of the sword as a means of conversion.

It was during the dark ages that the Mu’tazilites were suppressed. Their teachings were made a crime and those of Aristotle were lost to the Muslim world. Instead of focusing on Allah’s omniscience, the new Islamic scholars focused on his power and on his omnipotence.

The result of this focus can be found in the 11th century writings of Abu Hamid al-Ghazali. Al-Ghazali rejected all Greek thought and writing about the Mu’tazilites he said: ‘The source of their infidelity was their hearing terrible names such as Socrates, Hippocrates, Plato, and Aristotle.’

In his major work, The Incoherence of the Philosophers, al-Ghazali consolidates the change:

God is not bound by any order and that there is therefore, no ‘natural’ sequence of cause and effect, as in fire during cotton or, more colourfully, as in ‘the purging of the bowels’ and the using of a purgative. Things do not act according to their own natures but only according to God’s will at the moment. There are only juxtapositions of discrete events that make it appear that the fire is burning the cotton, but God could just as well do otherwise.

In other words, there is no rational order in the universe on which we can rely, no rational deduction of cause and effect is possible. The result, al-Ghazali wrote, is that man cannot know moral principles of right and wrong through reason; only through revelation by Allah. A true believer, therefore, will devote himself to reading the Qur’an, the Divine path, so that whatever he does is an expression of and justified by Allah. After 9/11, Osama bin Laden agreed: ‘Terrorism is an obligation in Allah’s religion.’

Whether through cowardice or ignorance, few Christian clergy attempted to defend Pope Benedict from the irrational attacks; but perhaps an adequate defence requires a certain level of scholarship which is almost unknown elsewhere in the Christian world at these times.

Islam’s abandonment of Aristotle and reason, and its assumption of Allah as unreason is evidence of its abandonment of common sense; for Aristotle has always been known as the spokesman for common sense.

A similar lack of common sense was on open display just days ago in the Church of England which ordained an openly non-binary priest. By its ordination of a man who defines himself as gender-queer, the Church of England has retreated from Christian scripture.

Benedict was unique among all Christian clergy being able to justify Christian dogma with reason but without being dogmatic. The violence of the Islamic reaction to Benedict’s speech provides an insight into the problems faced by Western nations integrating its Muslim community and de-radicalising those within it who favour war over peace.

The Christian approach of which Benedict was the representative required justification by good deeds, which does seem to me to be just common sense.