I am sure that, like me, you have not only used the term ‘common sense’ yourselves, but have heard many people call for the use of ‘common sense’ when discussing certain topics. The question is, does saying some topic needs ‘common sense’ add anything to the discussion, or is it just one of those throw-away lines to which people resort when they have nothing further to offer on a subject?

Australia’s High Court has used the term over 1,400 times in its written judgments. Given the vast variety of legal cases in which the Court has used ‘common sense’ as an authority for some proposition, it is obviously a strong authority in a very wide domain. Whether that is because their Honours merely invoked it when there was no legal principle and needed a magical fix-it without really understanding it, is difficult to know.

In fact, if the syllogism is the principle that connects human reason to the truth, ‘common sense’ is the rational assumption where every valid syllogism begins, for it correctly identifies the major factual premise with which human rationality is concerned; eg., whether a person’s hair is red or brown, their voice is high or low, the water is hot or cold, or the meal is sweet or salty.

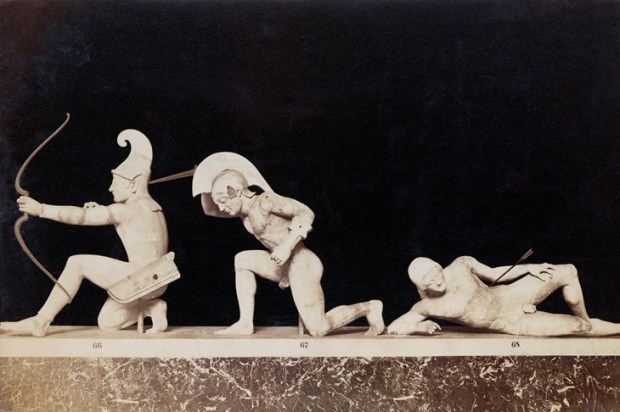

Human beings have five senses which connect us to the world by informing our body of a variety of sensations that our minds then consider. Plato explained this cleverly when he had Socrates hold up three fingers, describing them differently as ‘the smallest, the second and the middle: size, number or place’.

Once the intellect identifies that a particular finger was seen, that decision is shared in speech conveying, for example, that an index finger was seen. While our sensations and feelings are unique to each individual, rational speech shares a meaning that we have in common. This commonality in thought is what is meant by common sense.

By bringing conflicting sensations before our intellect, a decision is made that resolves conflicting sensations to give us a sense of the truth. That truth, when expressed in a language that is common to a people, is the common sense of the thing. ‘Common sense’, therefore, is essentially a reasonable explanation of facts that we first experience through our senses.

The birth of a child provides the first opportunity for a doctor to see a baby’s genitalia from which she declares the sex of that particular child based on the first-hand evidence of her senses, reasonably understood. That declaration, that someone is a boy or girl, is ‘common sense’ based on visual evidence. It is also objectively true and can be verified independently by other means and then reported. That is the benefit that common sense brings to any dispute.

Unfortunately, we live in an age when common sense is under challenge from unfounded opinion; opinion that is denied and defied by the evidence of the senses.

A person’s assertion of being transgender, a gender unrelated to their birth sex, is an opinion that is contradicted by the evidence of their sex at birth. Since the discovery of the double helix by the scientists Crick and Watson in 1953, it has been known that the male carries two chromosomes, visually identifiable by their shape as X&Y and that the Y chromosome determines the external male anatomy.

Were someone to claim in a court of law that they are not human, that they feel they are a cat, their feelings would be ignored. The judge (and jury, if present) would rely on the evidence of their senses to arrive at the common sense conclusion that the creature is human. They could even insist on identifying the sex of the human, if the facts of the case required it.

Thus, to assert a female gender due to a feeling of otherness when a person is born a male is to say, as the philosophers might put it, ‘the thing that is not’ as it was once described; in other words, to lie.

One of the signs of human maturity is the ability to correctly identify feelings so as not to lead to wrong opinions about them. It is the truth that every parent knows: the longer a child is allowed to hold wrong opinions, the more difficult it is to correct them. That is why children are sent to school and after, university. It is also why it is very difficult to change opinions held by university professors, especially those in law and the social sciences in general. They have believed their pet theories to be correct for so long, those opinions have become set in stone and their academic reputations hang in the balance if they are challenged.

Four hundred years ago, it was the great English philosopher, John Locke, the man who brought democracy and republican government to the English-speaking world, who said:

‘Would it not be an insufferable thing, for a learned professor, and that which his scarlet would blush at, to have his authority of forty years’ standing, wrought out of hard rock, Greek and Latin, with no small expense of time and candle, and confirmed by general tradition, and a reverend beard, in an instant overturned by an upstart novelist? Can anyone expect that he should be made to confess, that what he taught his scholars thirty years ago was all error and mistake; and that he sold them hard words and ignorance at a very dear rate.’ (John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, p. 545)

Putting all wrong opinions to one side for a moment, I would like to take this opportunity to wish you all a Happy and Holy Christmas and a safe and prosperous New Year.