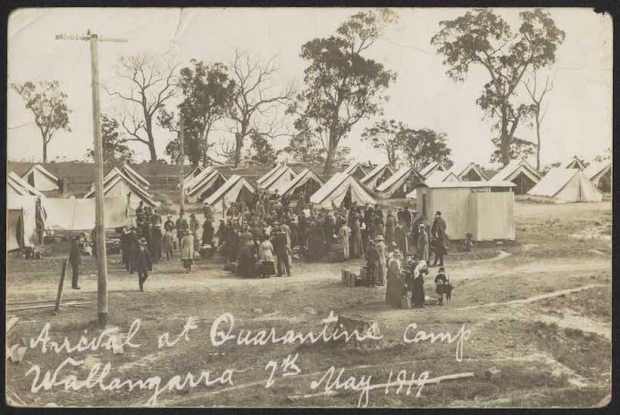

Infectious disease has been a deep-seated and inescapable feature of Australian life since the early days of settlement.

Over the last 235 years, the lives of many Australians have been swept up in outbreaks of infectious disease. Such events focused attention on the insecurity of everyday life and were a regular reminder of risk and the presence of death.

Many outbreaks of infectious disease captured public attention and were responsible for great outpourings of fear, hysteria, and panic. They also served to highlight the importance of the biophysical environment around us as well as human mobility, general living conditions, and in many cases, the need to pursue vaccination. Importantly, they also put to the test how we responded as well as challenging our government’s comprehension and management of such events and frequently found it wanting.

Infectious disease place in sharp perspective the everyday workings of Australian society, often removing the veneer people erect around their lives, revealing them as they really are – fearful of infectious disease, wary of contact with ‘others’, anxious about threats from ‘outside’, searching for someone to blame, and always sceptical of our government’s ability to protect us.

In 1969, the US Surgeon-General proudly announced to the American nation that infectious diseases had finally been conquered and that the time had come to move on and address a wide range of chronic diseases such as Cancer and Heart Disease. As many breathed a sigh of relief and indulged visions of a new anti-infectious age, new infections were already appearing in parts of Africa and Asia. Over the next few decades, not only did a wide range of childhood infections such as Measles and Diphtheria persist, but an endless parade of so-called ‘new’ infections appeared – La Crosse Encephalitis, Lassa Fever, Hantaan Virus, Ebola, AIDS, West Nile Virus, SARS, Bird and Swine Flu, and Coronavirus.

The hope of an antiseptic and infection-free age was simply swept away.

Added to all of this was the persistence of a range of mosquito-borne infections such as Dengue Fever, Murray Valley Encephalitis, and Ross River Fever. One might be excused for saying that our 21st Century differs very little from the centuries that preceded it.

There seems little doubt that our hopes of a disease-free Australia have also proved to be illusionary. Epidemics and pandemics are not a thing of our past, as the last 22 years demonstrate conclusively. Infectious disease continues to batter us where hardly a month goes by without the report of the emergence or re-emergence of a new infectious disease threat.

We have severely underestimated the importance of the biophysical environment and how it dominates our lives. The microbial world is a continually changing and adapting, a situation which we continue to under-estimate believing that we are the world’s dominant species with the power to control everything. But have we ever won the battle against infectious diseases and managed to remove the continuing threat to our lives? I very much doubt it.

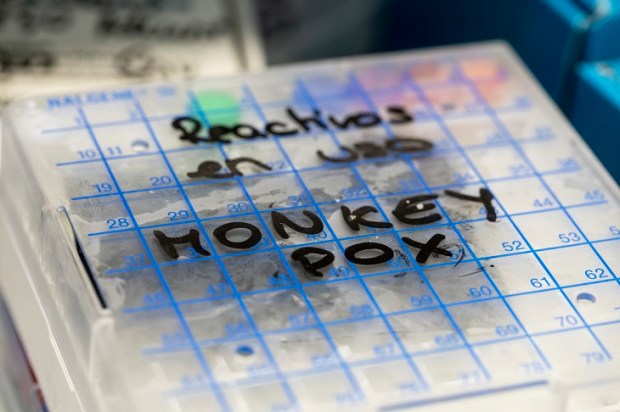

Smallpox was claimed to be our only true victory over infectious disease, but Monkeypox is currently showing the price we paid for this. Most of us also believe that Bubonic Plague is a thing of the past but in truth, Bubonic Plague is geographically more widespread today than at any time in human history and between 1,000 and 2,000 cases continue to occur every year. Polio is another example where we claim victory over infectious disease following the advent of the Salk and Sabin vaccines after 1956 only for variants of the disease to reappear in recent years. Malaria also remains a threat throughout much of our world. In 2020, 241 million cases were recorded, the majority in Africa.

Over the last two centuries, our optimist assault on infectious disease rested on the assumption that we were confronting a stationary target and that we could simply level ‘magic antibiotic’ and ‘anti-viral’ bullets against it and win the battle. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

In Australia today, five major categories of infectious disease remain of importance.

Firstly, a number of ‘older’ infections persist among specific social groups of our population. Equal access to our health care facilities has never been shared by all Australians particularly those of lower socioeconomic status as well as some of the ethnic and racial groups. Many enjoy unhygienic and hazardous living and working conditions, possess limited resources narrowing access to healthcare facilities, and often inadvertently expose their children to health risks.

Secondly, particular human attitudes and behaviour such as avoidance of vaccination can expose people and their children to a wide range of infections.

Thirdly, the persistence of older viral infections for which no specific treatment or cure is available can cause high morbidity but usually low mortality such as Chickenpox and Influenza.

Fourthly, the emergence of ‘new’ viral infections such as Coronavirus for which in the initial stages no specific drug treatment existed.

Finally, the persistence of viral mosquito-borne infections such as Dengue Fever, Ross Rover Fever, and Barmah Forest Virus do not kill very many Australians and thus seem to be tolerated to a large extent. This particular situation may also help explain our failure to come up with a specific drug for such mosquito-borne infections where if we regard a particular infection as not life-threatening but simply disabling for a few weeks, we seem content to live with it.

Threats from infectious disease are not new. Australia’s history is littered with confrontations with major outbreaks of infectious disease, many of which lingered on for decades. It is interesting how little we seem to have learned from our past and how we still believe that infectious disease do not offer a threat to our life.

As Freud said 90 or so years ago: ‘Contemporary man, living in a scientific age in which infectious disease is understood and to a large extent controlled, is apt to lose appreciation of the enormous population losses in past generations and of the prolonged widespread psycho-social and emotional strain produced by such disasters.’ A very apt comment in these times of Covid as well as the persistence of many other infections.

Since the 1950s, broad changes have taken place in Australia with respect to patterns of infectious disease and the ageing of the population. These have directed public health attention away from the biophysical environment and infectious disease towards greater consideration of the relevance of the social environment for health, particularly the role of man-made toxicants, noxious social conditions, and unhealthy lifestyles.

Despite all these changes, many infectious diseases did not disappear. They remain widespread and an important factor in our morbidity. The persistence of infectious disease in Australia must, in many ways, be seen as a failure of our government and public health to come to terms with a series of basic problems such as appreciating that some members of our society have deeply entrenched health attitudes and health behaviour and that often people who are at the highest risk have the lowest regard for prevention and public health.

There is little doubt that maintaining Australia’s public health is a difficult undertaking at the best of times, requiring a difficult balancing act of two conflicting forces – individual rights and liberties on the one hand, and the overall wellbeing of all Australians on the other.

In times of major outbreaks of infectious disease such as Covid, the uneasy equilibrium between these two forces is easily upset. It reveals a basic weakness of Australia’s public health that this conflict has never been resolved.

Outbreaks of infectious disease often force us to consider priorities and choices such as freedom versus coercion and social responsibility versus individual rights. Perhaps it is time for our government and public health to address all these issues.