The World Health Organisation (WHO) has accomplished important work in its relatively long lifespan for an international organisation, including the eradication of smallpox. More recently, however, its ‘priorities have increasingly reflected the biases and interests of corporate medicine’. The pandemic treaty adopted last month will reward the WHO for its gross Covid mismanagement by strengthening the framework for global health cooperation under WHO auspices. The treaty sets out the principles, approaches and tools for the international coordination of the global health architecture for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response. It will open for signature and ratification next year, if and when the Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing (PABS) system is negotiated, drafted and adopted.

What follows is a five-part analysis of (a) the low salience of pandemics as a health risk, (b) WHO’s Covid failures, (c) the reality of major disease burdens disaggregated by income levels of countries, (d) the dilution of sovereignty by the globalisation of health, and (e) the need to rebalance health sovereignty through subsidiarity as the organising principle of the distribution of responsibility, authority and resources for health decisions. The article concludes with an assessment of the impact of the US exit from the WHO.

1. The Threat Salience of Pandemics

The pandemic accords focus on building a global surveillance system to detect emerging pathogens and respond swiftly with coordinated measures, including the development and equitable distribution of medical countermeasures. Yet, the premise of the accords is an inflated account of pandemic risk that is simply not supported, neither by historical evidence nor indeed by the experience of the last five years. As a result, its effect will be to badly distort health priorities away from the real health needs and other social and economic goals of many countries.

Using figures from Our World in Data, in the 125 years since the Spanish flu, a grand total of 10-14 million people have died around the world in pandemics: Asian and Hong Kong flu (1957–58, 1968–69), around two million each; swine flu (2009–10), 0.1-1.9 million; seventh cholera pandemic since 1961, 0.9 million; Covid-19 (2020–24), 7.1 million.

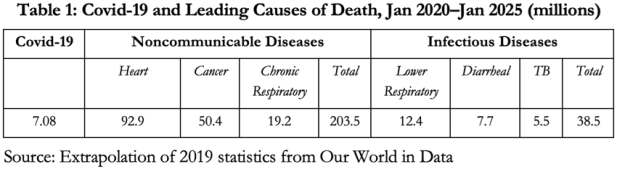

Nor did Covid pose an overwhelming threat even during the last five years. Of the 55 million total global death toll from all causes in 2019 (the last year before Covid) alone, 7.7 million people died from non-Covid infectious diseases. Another 40.7 million deaths were caused by non-communicable diseases. The three leading causes of deaths were heart diseases (18.5 million), cancers (10 million) and chronic respiratory diseases (3.8 million).

If we do a simple linear extrapolation, that means that in the same five-year period since January 2020 in which 7.1 million people died with Covid, about 203.5 million people would have died from non-communicable, and another 38.5 million from non-Covid infectious diseases. It’s worth emphasising that the Covid death toll refers to deaths with Covid. Deaths from Covid would have been considerably fewer.

Based on these historical data and wider perspective, was it prudent health policy or medical malpractice to repurpose national health services into de facto Covid health services? What percentage of the world’s total health budget should be spent on pandemic preparedness, prevention and response? Would a higher percentage benefit the world’s peoples or the WHO? Do we really need yet more national and international bureaucracy and meetings: national committees for implementing International Health Regulations (IHR) plus periodic Conferences of States Parties?

These are the questions and considerations worth bearing in mind when discussing the newly adopted pandemic accords. Indeed, do the three years already devoted to meetings and negotiations on the pandemic accords not amount to a diversion of time, effort and resources from more urgent health priorities – opportunity costs?

2. WHO Covid Failures

Speaking at a media briefing in Geneva on March 3, 2020, WHO Director General (DG) Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said that Covid’s case fatality rate (CFR) was 3.4 per cent, against under 1 per cent for seasonal flu. Addressing an internal meeting on April 7, 2025, he said: ‘Officially 7 million people were killed [by Covid], but we estimate the true toll to be 20 million’.

The two statements, delivered five years apart as bookends to the pandemic, amount to self-serving catastrophisation and fear-mongering. They underpin efforts to commandeer even more powers and resources for future pandemics to be declared on the sole judgment of the DG. Like New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern, the WHO must be revered as the single source of pandemic truth for the whole world.

Yet, DG Tedros’s judgment on such matters is demonstrably flawed. He unilaterally declared a global emergency in July 2022 over monkeypox after just five deaths. This was lifted in May 2023 after a worldwide total of 140 deaths. To grasp just how farcical this was, consider: an average of 501 Australians died daily in 2023, 140 Australians (the worldwide total of monkeypox deaths by the time the global emergency was lifted) died by suicide in 16 days, from accidental falls in three weeks and in road accidents in six weeks.

As per the WHO’s own constitution, ‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.’ In responding to a pandemic, there is a trade-off between public health, individual wellbeing and economic stability. It is the responsibility of health experts to focus solely on the first. Governments have the duty to balance all the competing demands and expectations and intuit the social fulcrum: the sweet spot at the intersection of dangerous complacency, alarmist panic, and reasonable precautions.

Almost all the Covid mistakes and damage can be traced back to two extreme but mutually contradictory assumptions, neither of which was ever revised back to the mean. First, assume the absolute worst about the pandemic on infectivity, speed of progression in the infected and in rate of cross-infection, lethality and lack of treatment options. Second, assume the very best about the effectiveness of all policy interventions, regardless of existing science and data (not GIGO computer modelling), careful analyses of risk profiles by demographic cohorts, and harms-benefits equation of interventions.

The WHO should have stepped in immediately as the international institutional firewall against this. It did not. Instead, its top leadership joined national health bureaucrats to insist they knew best and colluded in the takedown of dissenting voices by entering into partnerships with media houses and social media platforms. The consequences were catastrophic and have caused lasting damage to public health.

The WHO failed the peoples of the world in becoming a cheerleader for panicked responses instead of holding the line on existing science, knowledge, and experience, as summarised in its own report of September 2019. It proved too credulous of early Chinese data on no risk of human-human transmission, no Wuhan lab origin, lethality, and effectiveness of brutal containment measures. The first WHO panel to investigate the origins of Covid was riddled with conflicts of interest of key panel members and gave China a free pass. A follow-up investigation was stymied by China’s refusal to cooperate, for which it hasn’t been held to account.

Other WHO sins of commission included exaggerations of Covid lethality by presenting highly inflated estimates of fatality rates; obfuscation on the age-stratified risk profile of Covid mortality; unscientific and evidence-free recommendations on mask mandates and vaccine passports; and complicity in the human rights abuses committed in pursuit of the fool’s gold of Covid eradication.

Sins of omission included downplaying warnings of short and long-term health, mental health, educational, economic, social and human rights harms of the drastic interventions. School closures, for example, have created a generation of pandemic children in the hundreds of millions.

Avoidable non-Covid deaths escalated through disrupted food production and distribution globally; interrupted childhood immunisation programs; deferred and cancelled early detection programs and treatment of cancers; and deaths of despair of elderly people cut off from the emotional support crutches of loved family. The inflationary spirals are yet to subside from government support schemes to compensate for loss of incomes owing to economic shutdowns. The dramatic erosion of trust in public health institutions has lowered Australia’s childhood vaccinations to alarming levels, the ABC reported on May 16.

3. The Distribution of Disease Burdens by Income Levels

According to statistics reported by Our World in Data, on life years lost by people in low-income countries because of premature death, disease or disability, 56 per cent was from infectious and 35 per cent from non-communicable diseases. For high-income countries the figures were 10 per cent and 81 per cent, respectively. To better capture this empirical reality of sharply differentiated health vulnerabilities, we need devolution, not more centralisation, with the principle of subsidiarity determining the distribution of authority and resources at the different levels.

4. Sovereignty v Globalist One Health

Whoever thought it was a good idea to give any bureaucracy and its head the power to declare a pandemic emergency that will expand their reach, authority, budget, and personnel and shift the balance of decision-making away from states to an unelected global bureaucrat? Or to adopt a One Health approach when the empirical reality is of sharply differentiated health vulnerabilities, nutritional deficiencies and disease burdens between regions?

In combination with the amended IHR that come into force this September and which must and will be read in parallel, the political reality is that member states will be enmeshed into the international pandemic management framework led by international technocrats who lack the legitimacy of democratically elected political leaders, are not in practice accountable, and who have been given this enhanced directive role without meaningful parliamentary scrutiny or public debate by citizens.

Nothing in the Covid experience inspires confidence about the willingness and capacity of political leaders to resist WHO recommendations in this global institutional milieu. Rather, a de facto realignment of chairs at the decision-making table will see the experts take up positions at the head of the table instead of merely being present at the table to aid and advise on but not set health policy. This is why the pandemic accords are the latest waystations on the journey to an international administrative state that consolidates the globe-spanning ‘new pandemic industry’.

We need to do a better job in locating the sweet spot between inward-looking nationalism and sovereignty-destroying globalism.

5. Health Sovereignty and the Principle of Subsidiarity

Health policy and healthcare that use subsidiarity as the organising principle would begin with individual agency and autonomy, informed consent and prioritisation of patients’ individual health outcomes over collective public health benefits. The doctor-patient relationship in the clinic has to be sacrosanct and inviolate. If medical regulators violate that sanctity to invade the clinic, for example by prohibiting the doctor from discussing risk of collateral harms because this could increase vaccine hesitancy, they destroy patient faith in the doctor’s professional integrity, increase public distrust of health experts and promote cross-vaccine hesitancy. All this has already happened and been documented in multiple polls in several countries.

Medical and drug regulators should prioritise patient safety over every other consideration. On this criterion, there was the unacceptable dereliction of the duty of care during Covid. To enable emergency use authorisation of vaccines, regulators hugely exaggerated health risks and threats, refused to draw accurate risk profiles by age and regions, dismissed legitimate concerns and questions about side effects and harms, condemned efforts to identify promising possible repurposed drugs as dangerous, and short-circuited the normal multi-year stringent safety and efficacy trials. Remarkably, all this was done based in pseudoscience and voodoo science.

Governments abdicated responsibility for pandemic policy to their health bureaucrats. The latter deferred to the international technocrats in and around the WHO. Thus they acted on the basis of the very opposite of the principle of subsidiarity, from the individual and the state to the regional and the global.

The US Exit is a Wake-up Call

Before empowering the WHO to cause even more harm, we should first investigate its Covid failings and decide if major reform can overcome the accumulated vested interests or if we need a new international health organisation. Any organisation that has been around for nearly eight decades has either succeeded in its core mission, in which case it should be wound down out of existence. Or else it has failed, in which case it should be abolished and replaced by a new one that is more fit for purpose for today’s world.

The WHO confronts a $2.5 billion shortfall between 2025 and 2027. Its financial situation is not helped by President Donald Trump’s decision to pull the US out. Explaining why, Health Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr says that the WHO has been corrupted by political and corporate interests and ‘is mired in bureaucratic bloat’. ‘Too often it has allowed political agendas, like pushing harmful gender ideology, to hijack its core mission.’ The pandemic agreement ‘will lock in all of the dysfunctions of the WHO pandemic response’. ‘We want to free international health cooperation from the straitjacket of political interference by corrupting influences of the pharmaceutical companies, of adversarial nations, and their NGO proxies.’

That is a clear and compelling rationale put forward by Kennedy for the US withdrawal from the WHO. As in most areas in the current era, the United States has the heaviest normative weight and strongest gravitational pull of any country in the world. For better or worse, the presence of the likes of Robert F Kennedy Jr, Jay Bhattacharya, Marty Makary, and Vinay Prasad in the top echelons of public health decision-making in Washington DC is bound to have ripple effects in other countries in recalibrating the normative settling point of national and global public health policy.

Moreover, the US exit from the WHO does not necessarily signify a retreat from the commitment to international cooperation in shared health goals. In a joint statement on May 27, Secretary Kennedy and Argentina’s Health Minister Mario Lugones announced an initiative to launch a new alternative to WHO. They explained that the two countries’ withdrawal from the WHO was due to the organisation’s ‘increasing politicisation’ and the ‘absence of meaningful reforms’: ‘increasingly reliant on voluntary contributions and vulnerable to the influence of non-scientific agendas’, the WHO ‘has shifted away from its founding mission’. That said:

Withdrawal marks the beginning of a new path – toward building a modern global health cooperation model grounded in scientific integrity, transparency, sovereignty, and accountability. Our shared commitment is to cost-effective, evidence-based public health interventions that prioritize prevention, especially in children, by addressing root causes such as environmental toxins, nutritional deficiencies, and food safety standards.

The international managerial-technocratic elite (the ‘lanyard class’ of officious, rules- and process-obsessed professional cadre that runs the national public sector and international secretariats) will circle the wagons to defend the expansion of the international administrative state. The political leaders in thrall to the expert class will genuflect to their advice. Those seduced by the idealism of international solidarity and others corrupted by the lucre of pharmaceutical lobbyists will not be persuaded by the Kennedy-Lugones diagnosis of what ails the WHO and their vision of a replacement international health organisation.

Competent leaders of self-confident countries, however, should take up the offer to nest the ethic of global health cooperation in a new specialised international organisation that better respects the health sovereignty of member states and the health needs of people. Other countries too should join the US to shift the focus to chronic diseases that sicken peoples and bankrupt health systems. This will better serve the needs of people instead of aiding and abetting the pharmaceutical industry’s goal of profit maximisation.

This article draws together thoughts from two recent interviews by the author. The first, with Topher Field on June 2, can be found here. The second, a panel discussion with the Aligned Council of Australia on June 5, can be found here.