Sydney’s Macquarie Law School is attracting public criticism for compelling law students to include Acknowledgment of Country (a form of political speech) in work to which it has no relevance. It’s a change from the history of law schools as the entry point to a financial cabal.

The legal profession in Australia (with some notable exceptions) has not and is not covering itself in glory. There are several issues on which we can judge the judges, prosecute the prosecutors, and police the police.

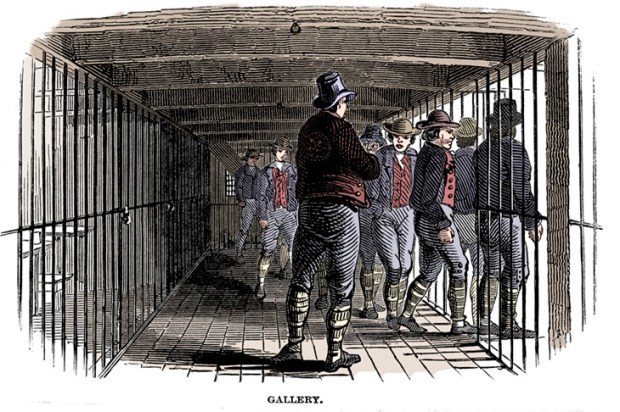

For instance: silent and inactive on wrongful convictions, the profession across all jurisdictions shirks its responsibilities as a self-ruling profession while enjoying professional immunity. After failed appeals, innocent accused often spend years, sometimes decades, behind bars with the legal profession exhibiting no sense of urgency to properly or fully examine their cases. Well, maybe there is not enough money in that, with private resources exhausted and public defender fees rather modest.

If you think me too cynical, I refer you to Professor Lester Brickman, of New York’s Cardozo School of Law, who said in 1997: ‘When the ethics rules are written by those whose financial interests are at stake, no one can doubt the outcome.’

Brickman’s remark is reproduced in the late Evan Whitton’s meticulously researched and damning work, Our Corrupt Legal System (Book Pal, 2009).

Here’s another: Associate Professor Benjamin Barton, of the University of Tennessee College of Law, put the question, ‘Do judges systematically favour the interests of the legal profession?’ in the Alabama Law Review of December 2007. In what may be termed the Barton Hypothesis, he answered his question thus on page two of his 52-page (14,821 words) paper:

‘Here is my lawyer-judge hypothesis in a nutshell: many legal outcomes can be explained, and future cases predicted, by asking a very simple question: Is there a plausible legal result in this case that will significantly affect the interests of the legal profession (positively or negatively)? If so, the case will be decided in the way that offers the best result for the legal profession.’

Long before these law professors, Charles Dickens knew this, as we find in Bleak House (1853): ‘The one great principle of the English law is, to make business for itself. There is no other principle distinctly, certainly, and consistently maintained through all its narrow turnings. Viewed by this light it becomes a coherent scheme, and not the monstrous maze the laity are apt to think it.’

Or as Professor Fred Rodell, of Yale Law School, in Woe Unto You, Lawyers! (1939) put it simply, ‘The legal trade, in short, is nothing but a high-class racket.’

Closer to home, Sydney lawyer, Stuart Littlemore, stated lawyers’ ethics accurately when Andrew Denton interviewed him on Channel 7, in October 1995:

Denton: It’s a classic question. If you’re in a situation where you are defending someone who you yourself believe not to be innocent – can you continue to defend them?

Littlemore: Well, they’re the best cases; I mean, you really feel you’ve done something when you get the guilty off. Anyone can get an innocent person off; I mean they shouldn’t be on trial. But the guilty – that’s the challenge.

Denton: Don’t you in some sense share in their guilt?

Littlemore: Not at all.

Now, let’s take a hypothetical example in the spirit of prosecutors working a circumstantial murder case. Mister Crown makes every effort to bring in as much material as he can that could be attached to his case, presenting it to the jury in long, convoluted speeches … ensuring the trial goes as long as possible. Members of the legal profession paid by time benefit. A side benefit may be that snowing the jury with overwhelming arguably irrelevant material might well result in a guilty verdict … an appealable guilty verdict. Appealable due to speculation by Mister Crown … which the trial judge has failed to throw out. The appeal/s mean more work for the profession. Double whammy.

As for contributing factors to wrongful convictions, the most depressing aspect of so far unique research is that police are at the top of the table, with 55 per cent of the 71 total cases studied by Dr Rachel Dioso-Villa, at Griffith University Innocence Project.

But judges are not much less responsible in second worst place, with 32 per cent. Prosecutorial contributions to wrongful convictions are also a troubling 17 per cent. (They make judges look good…)

These figures show that police, prosecutors, and judges all contribute in varying degrees to wrongful convictions, sometimes/often cumulatively. That’s the opposite of the desired objectives of the justice system.

And now Macquarie Law School wants to force students to be even bigger hypocrites.

It makes you wonder why the legal profession has such high regard for itself?