Indoctrination is simply hypnosis stripped of its mystique. In our society, we experience a form of ‘mass hypnosis’ that does not travel through magical waves but through the data waves of the internet, streaming services, and social media. It is disseminated not by chants but by slogans, hashtags, and viral content. Its purpose is not to leave one unconscious to steal their wallet, but to enable a much greater theft – one that sustains economies by commodifying people’s behaviours. With debates surrounding AI regulation, data privacy breaches, and the impact of screen addiction – such as Australia’s under-16 social media ban – making headlines, this ‘mass hypnosis’ has become an unavoidable force in shaping our interpersonal relationships and identities.

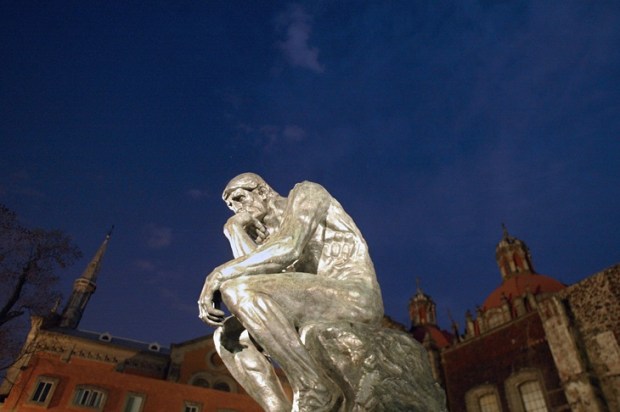

The content now entering our senses only amplifies the busyness of modern life; it does not encourage the introspection once inspired by the literature and music of the past. The noise of our time has made it increasingly difficult to access the quiet of one’s mind – from the monotonous, repetitive rhythms of computer-generated music to the mind-numbingly trivial quality of social media reels. Conservative philosopher Roger Scruton once referred to the content we consume today as a ‘pollution’ of the mind, discussing how the soullessness of electronic music points to a broader decadence. There is an indoctrinating force brought about by modernity that compels us to pursue shallow content and undermines thoughtful reflection.

The short-form content being mass-produced on social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram promote habitual scrolling and a feeling of instant gratification. While technological advancements have improved our lives in a myriad of different ways, they are also complicit in conditioning people to move from one distraction to another. In a 1961 BBC interview, writer Aldous Huxley observed that, far from being in control of growing technology, people have become the ‘victims of [their] own applied science’. Huxley could not have predicted the emergence of a piece of technology small enough to fit in our hands, an invention that, if he had heard of it in his time, might have been interpreted as both utopian and dystopian.

While sensationalism existed before the smartphone, primarily on television, the fact that technology has become so personal and follows us wherever we go evokes a scene from Brave New World – despite the novelty of such innovation. With algorithms feeding us content certain to bring momentary pleasure or reinforcement of our pre-existing beliefs, we have slowly been deprived of critical thinking. Personalised ads have also pandered to our desires, as a result of our data being sold to multi-billion-dollar companies over the years without much objection.

The ability to think reflectively has become rare in a society where many are preoccupied with entertainment. Even those who had the fear of becoming glued to screens are pushed in that direction as they keep up with the times. What fuels the ‘mass hypnosis’ is a desire to conform, as individuals willingly place their minds for sale to appeal to the sensibilities of others. The name ‘FOMO’ (fear of missing out) has been casually given to this phenomenon, making it sound like less of a threat to individuality than what it actually represents.

Today, there has come a trade-off between technological progress and individual freedom. People struggle to distinguish between the superficial but immediate satisfaction brought by technology and real happiness derived from personal fulfilment. As we embark on a new chapter with the emergence of both generative AI and advanced algorithms, our interpersonal relationships have suffered, as these technologies have become increasingly effective at stealing our attention. Short and entertaining videos on TikTok appear innocuous at first glance; however, the AI algorithm being used by the platform has been trained to maximise engagement, keeping users on the app and device for as long as they can. The internet and social media have also promoted a certain artificial happiness, measured by the number of followers and the public display of material wealth.

While government bans on social media in Australia would inevitably cause children to find workarounds – for instance, the discovery of loopholes in adult verification on devices – the actual solution lies in tackling the technological shift head-on by instilling greater critical thinking skills. Adequate education should equip us in rallying against such ‘mass hypnosis’, which will preserve our individuality and emotional connections with others. Improving media literacy among youth and reading works of dystopian fiction, such as the ones by Huxley, can help us recognise where our technology is heading and its potential implications if we are not careful in how we use it.

Although critical thinking skills are being taught in schools and universities, most people are already trapped in their devices from an early age, consuming repetitive content. This early indoctrination highlights the growing significance of teaching these skills even earlier in life. We have transitioned into an age of digital sedation, where we are to endlessly consume fleeting content. Fast-paced technological advancements have formed a new culture, one where everyone is absorbed by the busyness around them without actually noticing. The only way to break these chains is by returning the component of criticality to our thinking.