Is the story of Australia a horn of plenty or a cornucopia which we systematically fail to celebrate each year on Australia Day? Or fail to tell in non-existent documentaries about nation building?

Our early, lasting, and successful democracy; our first world economy which sustains the comparatively high Australian standard of living; and the functional health and education system (and other aspects of the ‘safety net’ for citizens) provide an answer. The answer is ‘yes’.

Although everything these days is contentious.

The first world economy sustains the wages of ordinary people. It began with the ‘squatters’ riding out of Sydney with sheep and gangs of ruffians. They occupied vast tracts of ‘Crown land’.

Aboriginal people had different views. The Kaurna in 1841 Adelaide asked for rations, land, education for their children, and respectful treatment (The Australian Horn of Plenty, Routledge 2024).

Squatter land use meant that Australia ‘rode on the sheep’s back’ for 130 years. Wool was Australia’s main export from the 1820s to the 1950s, except for the 1850s and 1860s when gold was more important, according to Ian McLean in Why Australia Prospered.

The early settlers sweated their way through manual labour in Australian summers. They tried to sleep in bark huts. Women had children these huts with no medical attention. They took a bullock cart from South Australia to the gold fields, over 500 kilometres with no roads or bridges. Or they walked.

Mining was always important.

Wages could be good, but the Great Strikes of the 1890s put at the forefront of public concern exactly what a ‘fair wage’ was. The pastoralists were stricken by drought and recession; they consequently wanted to cut wages and ignore trade unions. Trade unions disagreed.

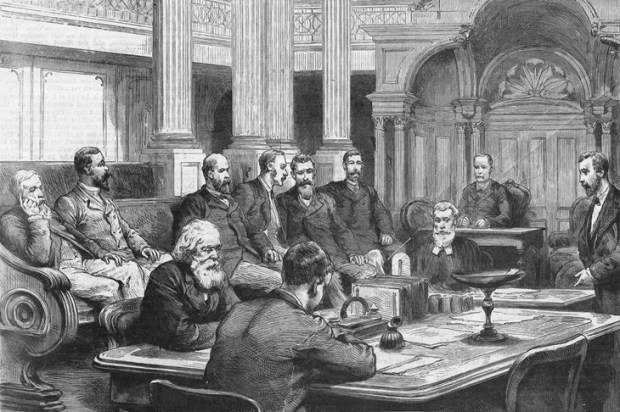

Then there was government. Agitators such as William Wentworth wanted self-government and generated a lot of support. To his growing concern this turned into a demand for democracy, one man one vote, and the secret ballot. The ‘spirit of democracy was abroad’ as he said, and as an old-fashioned Whig he did not support it.

Through his efforts, and that of many others, NSW, Victoria, and South Australia achieved self-government, one man one vote and the secret ballot in the 1850s. Local parliaments debated and drafted constitutions and electoral laws, authorised by the British authorities.

Aboriginal and Chinese men were given the vote at the same time, women in South Australia in 1894-1895 (and the right to stand for Parliament). A remarkable thing for the world of the time.

Wentworth and the Whigs had their revenge by setting up nominated or elected on a property franchise Legislative Councils to obstruct the more democratic Legislative Assemblies. Obstruct they did.

Although, they could not stop land reform, which gave ordinary people more access to the land. Parliaments were controlled mainly by fair elections and public opinion.

The Federation of Australia in 1901 was based on this early democracy.

The safety net of health and education was developed, at first incrementally with individual schools and hospitals, and later with more systematic government organisation.

The position of ordinary people was never assured. Henry Lawson warned in the 1890s that ‘blood’ would ‘stain the wattle’ if greed took the hard labour of ordinary people from them.

I would not apply the ‘DEI lens’ supposedly used by a leading candidate in the recent US Presidential elections (although not the winner). A more general, ‘We the people…’ is increasingly popular in the first world, while ensuring that all are included in citizenship. We should not simply ignore democracy, the first world economy, and health and education, or devalue it utterly.

Nobel Prize winners Acemoglu and Robinson in Why Nations Fail provide a long history of violence and theft in Africa and the Middle East, particularly after independence. ‘Government’ was often organised crime. There was often little point in working hard; someone would take it from you.

Spanish settlers in South America (in theory) had the same opportunities as our early settlers did. The rich plains of Argentina had vast pastoral industry potential.

Nevertheless, South America struggled with autocracy and government theft, and as a consequence, poverty. Most of South America eventually replaced dictatorial ‘Caudillos’ with parliamentary elections. But look at the struggle President Milei has in Argentina to restore prosperity or create it through market policies!

Look at the 35 wars in Africa (a current estimate), or the Arab Spring and struggle for democracy in the Middle East.

Why Nations Fail uses Australia, and other first world nations, as examples of how government can help prosperity by protecting property rights and the rule of law. They conclude that it is best if government is not organised crime.

Some think we are however systematically headed for loss of prosperity. Prosperity certainly is not guaranteed and automatic.

We need to focus on improving productivity across the board, from mining approvals to small business, to foreign investment, to cutting wasteful government spending. Taxes must be reformed to encourage initiative. These are the priorities, and we probably do not currently realise that.

We could ask Malarndirri McCarthy, Minister for Indigenous Australians, and the Shadow Minister, Jacinta Yangapi Nampijinpa Price, to sit in a room for a day with a notepad divided into two columns, one marked ‘agreed’ and one ‘disagreed’, to list practical measures only ‘closing the gap’ between Aboriginal people and others.

Then we should set aside a day to legislate (in each house of Parliament) the agreed practical matters. Set aside another day to debate the disagreed matters. Publish a report on the disagreed matters and argument, and let leaders justify it.

In doing so we have to fully respect the recent referendum, which was expensive and divisive.

The law of defamation is limited to people, not defaming the country or institutions as laws in some nations, even some in the EU and Nato. Our public debates are robust. Yet more civility is needed; the lack of it harms those who are disproportionate and defaming.

Our major parties share a common commitment to democracy, although some argue that attempts to regulate free speech are excessive and concerning. I personally think that they are.

Our major parties share support for the market economy and safety net of health and education.

No one would have the remotest chance of being elected to form a government that disagreed.

We have a lot in common.

Our national story on these issues should be properly told, not ignored. Most now speak of valuing our Aboriginal, British, and our multi-cultural heritage, including Noel Pearson quoted by the current Governor-General in her swearing-in speech in July 2024.

Why not celebrate what we have in common? And do so enthusiastically.