Concern about social media-based anxiety is popping up everywhere. Leaders of many kinds are talking about it, decrying it, and saying they will act on it.

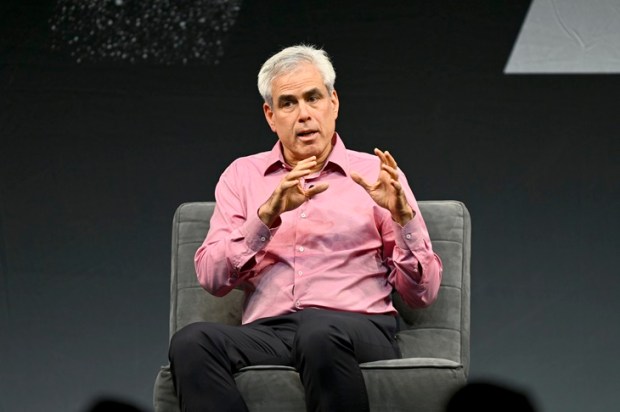

Jonathan Haidt who wrote The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness, must have some sense of satisfaction. I routinely hear his words being quoted. For example, ‘We under-protect our children on social media and over-protect them in the real world.’ Or, ‘Let’s avoid social media use until they are older.’

It seems that enough people are singing from the same song sheet for our Prime Minister to leap into action.

Given Albanese’s difficulty in explaining details, we are not sure what that his proposed action entails at this stage. Many people have raised concerns about the general idea of banning people of a certain age from use of social media on the internet. One main question is whether this sudden bout of compassion for the young is a stepping-stone into a greater monitoring and control of personal use of the internet – it is a fair question to ask of our government.

Another kind of questioning about this leap to legislation so that we can ‘keep them safe’ is about the incoherence it represents in how governments are currently treating other issues of ethics and human life.

For example, the same people pushing for this ban (because young people are, well, too young) also push for their freedom to ignore the ones responsible for caring for them (their parents) in their expression of their gender, including physically manipulating their bodies to align with their thought desires. Similarly, these same people will ignore requests to have inquiries into physical abuse in remote communities, or the treatment of babies (‘accidentally’) born alive and then left to die. They will ban vaping and increase tax on cigarettes to an intolerable level while destroying incentives for family life – things such as shared taxation for stay-at-home parents, developing controlled government spending and controlled immigration to help with house prices, and giving parents the ultimate say in the kinds of ethics and values they want taught to their children in state-run schools, let alone in faith-based schools.

But there is another aspect that I have not seen anywhere, despite the increased discussion around Haidt’s and others’ work. I call it the ‘Chapter 8 phenomenon’.

To understand where this unspoken dynamic starts, I suggest a reading of his Righteous Mind. Haidt uses the (initial) findings of his moral foundations framework to explain why different sides of politics have so much trouble hearing each other (and his proposals are still very apt today).

According to book, the Left of politics simply put more emphasis on one set of moral values which is different to the broader emphasis that the Right seems to have (these are generalities of course). One of the ‘outliers’ of the Right (and there are others) that is not on the Left, is that of sanctity. In this earlier work are comments like this:

…the very ritual practices that the New Atheists dismiss as costly, inefficient, and irrational turn out to be a solution to one of the hardest problems humans face: cooperation without kinship [emphasis in the original] … Putnam and Campbell put their findings bluntly: by many different measures religiously observant Americans are better neighbours and better citizens than secular Americans – they are more generous with their time and money, especially in helping the needy, and they are more active in community life.

What does this have to do with the growing anxiety of the young? Lots. Haidt continues this theme in chapter 8 of his Anxious Generation. Admitting his atheism up front but being honest in presenting what he sees in the research, he again notes that he needs ‘words and language from religion to understand the experience of life as a human being’.

What is Haidt seeing in his and others’ research? He is seeing that ‘certain religious practices’ (oriented to the ‘sacred’ and to the ‘transcendent’) keep making a difference. Indeed, in terms of anxiety that is induced from social media, he and others have reported that conservative Christians do much better than the general population. A number of these researchers are still exploring why.

Haidt’s summary of this phenomenon at the end of chapter 8 is probably as close an atheist will come to agreeing with St. Augustine, who reflected that ‘my soul is restless until it finds rest in thee’. Haidt’s version says this:

But although we [Haidt and his religious friends] disagree about its origins, we agree about its implications. There is a hole, an emptiness in us all, that we strive to fill. If it doesn’t get filled with something noble and elevated, modern society will quickly pump it full of garbage.

BUT – and it is a big ‘but’ – this is more than forgotten here on our shores. It is ignored. I could speculate on why, but I won’t. I will report that previously in my years attending psychology conferences, and asking why we were not investigating that which was being well reported across the seas (the constructive influence of being part of a sincere – respectful, invitational – religious community: this excludes the pretend religious and the anti-human religious), there was a consistent, ‘Oh, we just forgot.’ This started back in the 1980s when our colleagues in the USA and other places were seeing the helpful impact of attending a youth group. We labelled this effect as a ‘stress buffer’ back then – now it would be put in resilience or positive psychology terms. The same was reported for those with the dominant teenage body issue back in the day – anorexia.

It was also back in the 1980s that there was an Australian Psychological President (Prof. Ron King) who warned of such neglect of faith communities within the discipline. He was also ignored.

And thus today we have leaders who have shallow reactive heroism when faced with a teen problem – let’s make a law! Yes, it is good to help young people stay off social media (in contrast to the internet) until about 16 – or have the parents monitoring what is happening. Yes, it is good to not have social media devices in the bedroom. This is good for the young and their parents. But will we make laws for all of that?

What about identifying, encouraging and supporting youth activities that provide alternatives to living life via a screen? I doubt it. Our current leaders seem to be thoroughly uninformed about the kind of voluntary associations that help build belongingness, community and safety. Such places as sports teams, adventure groups (Scouts, Girl Guides, church youth ‘brigades’), dancing academies, community music performance groups, and yes, faith-based youth groups – all of these could help, and would be grateful for support in some way.

However, I think Haidt is correct. The Left cannot comprehend the need for something elevated and transcendent in our souls. So they go to their natural default – community by compliance, and not by invited commitment. If their proposed law is passed, it won’t work. Be prepared for even more drastic interventions into our lives.