Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) intends to declare a wide range of gene-edited foods substantially equivalent to conventional foods. They’re holding a consultation, and their concerns revolve around whether the new definitions are sufficiently clear.

FSANZ are describing it as a ‘paradigm shift away from the process-based understanding and regulation of gene technology used in food production to an outcomes-based approach’. But it is not being widely covered by the media in Australia or New Zealand.

The consultation, which ends September 10, focuses on ‘new breeding techniques’ (NBTs), also called ‘precision breeding techniques’ (in the UK) and ‘new genomic techniques’ (in Europe). Regardless of what new names they are given, they are GMOs.

FSANZ proposes that if there is no novel DNA in the genome edited organism, the organism can be excluded from the definition of GMO food. They’re looking for a single outcome – is the novel DNA present? They’ve done this, as they explained in a recent webinar, because this is a clear, consistent, and objective criterion, easy to comply with and enforce.

Small insertions and deletions that change the genome, would be outside the new regulation. These are included in the current process-based definition which captured food produced using gene technology.

In addition, with a broad stroke of their pen, they’ve decided to also exempt food additives, processing aids, and nutritive substances; substances used in cell culture, for the production of cell-cultured food, food derived from null segregants, and grafted plants.

With this proposal, none of these foodstuffs would need to be labelled as a GMO. Food may have changes from editing or inserted DNA from a crossable species, but if there is no novel DNA (under their definition), the food won’t be labelled. It’s considered by FSANZ to be ‘unimportant to safety’.

The effect would be a windfall for the technology developers (who hold the patents) and the increasingly concentrated agri-food system. The new definitions of genetically modified, engineered, or edited (the terms are interchangeable) GMO organisms upend historic risk assessment.

FSANZ’s pivot reflects their position that NBTs are substantially equivalent to conventional foods. In 2019, FSANZ conducted a safety assessment of NBTs compared to other methods of genetic modification and conventional food. The safety assessment concluded:

‘…over time, many considerable genetic changes have been introduced to food organisms using conventional breeding.’

What FSANZ appear unconcerned with, in my opinion, is the scale and pace with which NBTs can be developed in the laboratory and deployed into the environment, including into human bodies. It is important to understand scale and pace because risk assessment must not only identify hazards, the potential of an organism to cause harm to human health and/or the environment; but must concern itself with risk, the likelihood of a harm to occur and the severity of the estimated damage.

In this case, FSANZ do not discuss the global biotechnology revolution in the realisation of novel gene-editing technologies nor focus on the scaling up of laboratories, the proliferation of patent licensing, and the ‘faster development rate from bench to market’. Intellectual property rights are stronger for food produced using biotechnology than for conventional breeding techniques.

And what of scale gearing?

Risk must be considered along the entire technological trajectory. While there is a high level of consumer trust in FSANZ, we can only wonder what this shift away from considering probability and scale will mean for consumer trust.

FSANZ’s assessment of costs and benefits emphasised clearer pathways to market for the food industry and the potential long-term benefit to consumers from ‘cheaper, high quality, and new food products’.

It does not appear that this assessment considered the literature on consumer preference, nor the fact that studies across countries demonstrate that people actively select non-GMO food and are prepared to pay a premium for it.

Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, French, and American people prefer food that has not been genetically edited/modified. Social values, institutional trust, and awareness are important factors in public decision-making.

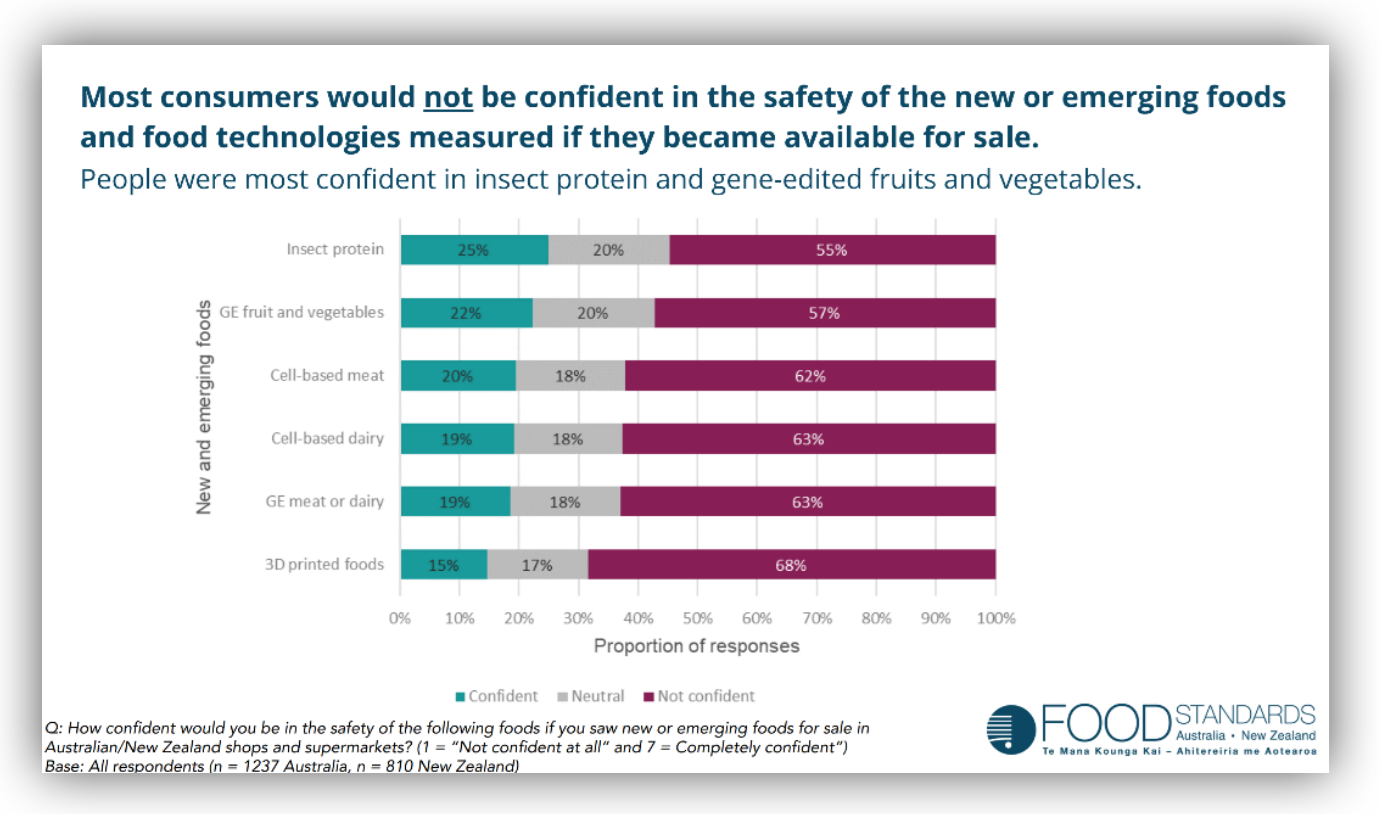

It is my view that FSANZ’s actions contradict global demand for non-GMO food. Even FSANZ’s 2022 Consumer Survey identified that people include NBTs as a continuum of GMOs, and that people are concerned about the long-term effects.

Figure1 2023 Consumer Insights, FSANZ.

Public concerns about genetically modified and edited food are reasonable. Food adulteration and food fraud for financial gain has a long history. Lack of consumer acceptance and trust in GMO foods is, in my view, downplayed in the proposal, which focuses on specific public knowledge relating to newer editing techniques. This belies FSANZ’s own research that found that level of knowledge, perceived or objective, was not correlated with level of support for GMOs.

It’s important to emphasise that despite years of biotech development, the traits that FSANZ hypothesises will provide wide benefit: ‘more sustainable food production, climate change resilience and mitigation, cheaper food’ bear no resemblance to the traits that have been commercialised. The vast majority of GM crops have no relevance to human health, yield, or resilience. Herbicide tolerant crops dominate the global GMO crop market. FSANZ is not required to evaluate the risk to soil, groundwater, and human health from the partner herbicides that the crops are designed to accommodate.

The P1055 consultation opened in 2021 when FSANZ proposed a hybrid approach, an expanded process-based definition. Views were divided. While 1,736 individuals and institutions responded, there was no disclosure of the balance of comment relating to particular questions, including the extent to which submitters wanted GMO labelling of all NBT foods. The balance of comment from the public and some university biosafety research centres was broadly ignored in the Stakeholder Feedback Summary Report.

In the response to the 2021 consultation, developers and industry told them that the approach was too complex. Croplife Australia stated:

‘We suggest that the guidance materials should present example scenarios to provide developers with further clarity. It may also be beneficial for the guidance materials to present the scientific rationale for the exclusion of some NBT foods from premarket assessment and highlight the risk-proportionate and product-based assessment process.’

J.R. Bruning is a sociologist (B.Bus.Agribusiness; MA Sociology(Res)) based in the Bay of Plenty, New Zealand. Bruning is a trustee of Physicians and Scientists for Global Responsibility (PSGRNZ). Bruning’s work explores the relationships between governance, policy, and the production of scientific and technical knowledge for public good.