From time to time, an event presages a change of more general significance than the circumstances appear at the time. This occurred when a constituent visited me more than two decades ago. In his early forties, quietly spoken and of Middle-Eastern background, he was accompanied by his daughter, a girl of about 12 years of age. His purpose was to press upon me the plight of the Palestinians. This he did with a quiet passion and empathy for his people. Representing an electorate that had both a mosque and a synagogue, as well as people from all of the great faiths, I had maintained a knowledge of events occurring in many countries around the globe. But this constituent had knowledge of a litany of recent events in the Middle East, more than one could know from following most of the media, including programs like the BBC World Service. Curious about his knowledge, I asked where he sourced his information. His reply lodged in my brain. ‘My family (referring to his daughter) only watch Al Jazeera,’ was his reply. It was in the early years of the Qatari-funded, Doha-based media organisation. ‘Don’t you also follow other media,’ I asked. ‘No,’ he replied. ‘We don’t trust the Western media.’

The man’s remarks have resonated with me over the subsequent years. It is not that the Western media – as a whole – is entirely objective and trustworthy. The integration of facts and opinion in news articles began a progression to the modern journalistic modes in which the two are often inseparable. ‘What is fact and what is opinion?’ is the question the modern reader has to ask always. This situation is compounded by the narrowing of acceptable opinion by many media organisations and the rejection of views not consistent with the zeitgeist.

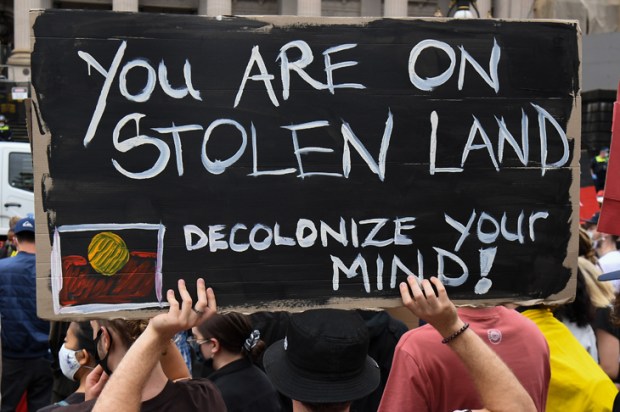

What troubled me at the time, and has done so ever since, was the sense that my former constituent’s views were entirely of a Palestinian living in Australia rather than an Australian of Palestinian origin and heritage. His place of residence may have changed, but his existence seemed still firmly entrenched elsewhere. This was unlike many of my other constituents who had emigrated to Australia. The Greeks and Italians built their clubs and churches and celebrated their ethnic festivals, but regarded themselves as Australians. As was the case with more recent arrivals, from Asia, Africa and South America. ‘I am an Australian of (such and such) ethnic background’ was the common refrain. But for many coming to this country in recent years, this order has changed. Many more people now act and speak with primary allegiance to their ethnic origin. It is a worrying trend.

The dangers of these developments to the liberal order were illustrated by Jonathan Sacks in a series of books and articles, many written some two decades ago. As a leader of a small group of people which has been discriminated against and persecuted more than most over the centuries, Sacks clearly understood the importance of toleration to a well-functioning free society. His critique of ‘multiculturalism’ – which has morphed from a political aspiration to live together in harmony to an ideology – is telling. Put succinctly, Sacks demonstrated how multiculturalism was incompatible with liberalism.

In The Home We Build Together, Sacks illustrates the challenge facing multi-ethnic nations by describing three ways in which people can ‘live together’. Reflecting his British background, the former chief rabbi of the Commonwealth describes the first as ‘society as a country house’. This ‘speaks about host and guests. There are insiders and outsiders, the majority and minorities. There is one dominant culture, and if you don’t belong to it, you don’t really belong at all. You are not “one of us”. This is the assimilationist model, known in early 20th century America as “the melting pot”. It says minorities must lose their identity in order to belong.’

His second model is the opposite: the hotel. ‘Minorities don’t have to give up their identities in order to belong, because there is no such thing as belonging at all. There is no one dominant culture; there is no one national identity. There are no outsiders because there are no insiders either. This is the multiculturalism model. The danger is that it turns society into a series of non-communicating rooms. It can lead to segregation.’

Sacks’ third model is ‘the home we build together’. This model ‘values the identities of both the majority and minorities. It says: ‘We are different, but that does not mean there is nothing to bind us in shared belonging. What makes us different is what we are; what unites us is what we do. We create the common good. Society is not static but dynamic. It is not just something we inherit and inhabit: it is something we make. The more different we are, the richer the possibilities of what we make together. That means seeing difference not as separation but as contribution. Yes, we have our private rooms, but we also have our public spaces, and those public spaces matter to all of us, which is why we work together to make them as expansive and gracious as we can. That act of making creates belonging. This is society as integration without assimilation.’

Sacks’ book is notably sub-titled ‘Recreating society’. Published in 2007, its central message resonates as much – possibly more – today than almost two decades ago. Britain, he wrote, had become a hotel. Reflecting on the terror attacks of 2005 and other events of the era, he argued for a return to liberal values. He was not alone. In December 2006, prime minister Tony Blair, in a speech entitled ‘The duty to integrate: Shared British values’, said there were limits to multiculturalism; that it was supposed to be not a celebration of division but of diversity; and the right to be a multicultural society ‘was always implicitly balanced by a duty to integrate…’. The events in Britain of the past months demonstrate how prescient were Sacks’ observations.

‘The real clash is between liberalism and multiculturalism. Liberalism is about the rights of individuals, multiculturalism about the rights of groups, and they are incompatible.’

Is this not what we have observed in our streets in recent years? Sacks argued that the rise of the procedural state, and managerial politics has resulted in society as a hotel. Neither liberalism nor multiculturalism has an overarching structure to encourage loyalty to a harmonious society, he maintains. What is required is an integrated diversity. ‘What we build should be the central topic of the democratic conversation, a conversation scored for many voices, covering many subjects, but unified around the question: what kind of society do we seek to create for the sake of our children and grandchildren, not yet born?’

Current events underscore the imperative of this discussion.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.