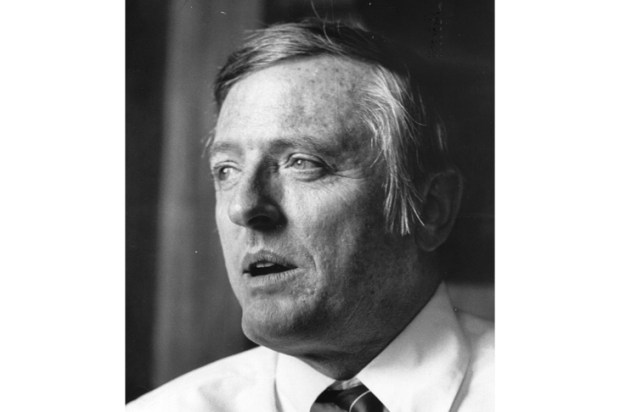

It’s sad to see that Sir Andrew Davis, the former head of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, has died. The man who became familiar to classical music audiences internationally when they saw him on television conducting the Proms brought the highest level of accomplishment to the position and we were lucky to get him. When you saw Andrew Davis conducting Handel’s Messiah you felt the sheer authority of the conception.

We should be gladdened by the fact that Jaime Martín the presiding conductor has achieved a record deal with the London Symphony Orchestra and will be bringing out an album of Debussy and Richard Strauss that should become a treasure to his fans together with the soprano Siobhan Stagg. Martín is a passionate extroverted conductor. His gesticulation is consistently and markedly flamboyant, as if every note of the music is an open invitation to the highest level of emotional intensity.

Is that true of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor which Melbourne Opera are mounting a production of from 8 May with Elena Xanthoudakis the soprano in the title role? The poet Peter Porter, a great lover of music of every kind but with a special feeling for the combination of words and music used to say, ‘It’s not so much a matter of bel canto as of can belto’ when he talked about the style intimately associated with the great singers (including not only Joan Sutherland and Pavarotti but also Maria Callas) who created the fashion for these roles.

It can be easy if you’re being cynical to say that Berlioz, the composer who his admirers say wrote the nearest thing to a literary masterpiece in his memoirs – as well as an extraordinary role for Jon Vickers in his operatic masterpiece Les Troyens – was right to say that Donizetti just wrote for Italians music as unthinking and easily digested as pasta.

In fact that’s not true of Lucia di Lammermoor and its untruth is underlined by the fact that the title role is closely associated with two very contrasted sopranos of the greatest eminence. With Joan Sutherland we are aware of the absolute purity of line, the sheer beauty of the singing, the elegance of how one of nature’s bel canto singers can inhabit a role – with all its romance and its deranged innocence (in the famous madness scene) – without getting down and dirty (so to speak) with the role. It’s easy to forget that Maria Callas the greatest singer-actress of her own (and perhaps any) generation looked at the start of her career as if she could become a Wagnerian and in her career in Italy she toured as Isolde and Brünnhilde and actually recorded the role of Kundry, that complex witch from Wagner’s Parsifal, and in a version conducted by Vittorio Gui with RAI National Symphony Orchestra with a cast that includes the legendary Russian bass Boris Christoff as Gurnemanz.

If you asked Richard Bonynge – Sutherland’s husband – about all this he would say the Wagnerian roles were throat-cutters and he did everything he could to keep Sutherland away from them. But Callas is an overwhelmingly powerful and dramatic Lucia – enraptured, heartbroken, starkly and startlingly mad as a snake. It is a stupendous performance and it takes the breath away in the early recording with Herbert von Karajan.

Callas became the epitome of the singer who made acting the natural framework for characterisations in which the singing was the musical expression of the drama, almost at all costs. She was the natural embodiment of everything Visconti and later his lieutenant Zeffirelli wanted to do with opera as a dramatic medium.

It will be fascinating to see what Elena Xanthoudakis makes of the gliding beautiful heartbreak of Lucia.

Another of Callas’s roles will be on show in a spectacular way with the production of Tosca at the Margaret Court Arena from 24 May. Tosca is one of Callas’s greatest roles and in Puccini’s opera she is pitted against one of the most sinister figures in the whole of opera, the savage and terrible police chief Scarpia who was famously played in the Callas productions by another great actor-singer, Tito Gobbi. He was the natural complement to Callas and his hubristic sadism is the perfect foil for her romantic idealism. Tosca is a very great opera because its bloody and terrible melodrama is given a transfiguring power by Puccini’s music. Tosca herself is a figure of compelling loneliness when she sings her great aria ‘Vissi d’arte’ but every note of the music is expressive of a dramatic action that encompasses torture, rape, stabbing and the act of a leading character throwing herself from the ramparts of the Castel Sant’Angelo.

And to see it in a famous sports stadium should be fascinating given the breadth of the drama it will show, to what it is hard not to imagine will be spectacular effect.

A different – though not unrelated – fascination awaits with Sarah Brightman’s Sunset Boulevard from 21 May. First an instant classic with Billy Wilder’s masterpiece of a film recapitulating the tragic ruination of Norma Desmond’s beauty. Then the original American stage production with Glenn Close and now the woman whose voice Andrew Lloyd Webber was in love with – the voice that betokened the music of the most romantic night. It will be fascinating to see the show again with Brightman’s quasi-operatic lyrical soprano calling the shots.

It was disappointing recently to turn with expectant glee to the National Theatre At Home app freshly acquired. Yes, there’s the Angels in America with Nathan Lane as Roy Cohn. There’s the first and one of the finest transcriptions, Helen Mirren as Racine’s Phèdre. There’s a production from just yesterday of Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba with that very great actress Harriet Walter, matching his Yerma with Billie Piper.

But there is not sign of arguably the greatest thing they ever did which was the uncut version of Shaw’s Man and Superman with Ralph Fiennes and Indira Varma (they are about to show in Macbeth). Man and Superman is one of the greatest things Shaw ever wrote with Jack Tanner (Ralph Fiennes) doubling as Don Juan and with all the central figures becoming their legendary selves in an immense dialogue in hell which deploys the most brilliant and incandescent dialectic Shaw ever wrote and it is performed with a lightning swiftness and power that is dazzling. So rescue it National Theatre at Home, your subscribers will cheer.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.