Australia’s suicide prevention policies are failing. We are falling behind the rest of the world when it comes to suicide prevention. From 2000-19 global suicide declined by 11 per cent. In Australia, rates increased by 31 per cent.

The reason? For many decades our health authorities have blatantly refused to target the group most at risk – men. Seven of the nine people who end their lives each day in Australia are male.

In 2019, the female suicide rate in Australia (5.6 per 100,000) while tragic, was similar to the rest of the world (5.4 per 100,000). However, male suicide rates in Australia (17.0 per 100,000) are now much higher than elsewhere (12.6 per 100,000).

The discrepancy is stark, and yet funding initiatives and bodies appear to fall short when it comes to targeting men who are most at risk.

Just look at the $1.8 billion of funding allocated in the 2022 National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement. This includes:

- $735 million for adult mental health services that generally reach twice as many women as men.

- $300 million for youth mental health services, which generally reach twice as many young women as young men.

- $465 million for aftercare support for people who attempt suicide, a model with a track record of helping more women than men.

- $35 million for suicide postvention support providing suicide bereavement services that predominantly support women.

It is hardly surprising that men feel as if they are being left behind. And when these programs do manage to support vulnerable men as a priority, the tend to invoke the toxic masculinity model in which men are told it is their fault the system is failing them because they are too stoic to reach out for help with mental health issues.

Yet here too there is big news.

There’s now statistical data to show that mental health problems are no longer considered the key risk factor for one of our major groups of vulnerable men. For the first time, this year the Australian Bureau of Statistics published statistics based on coroners’ reports showing relationship/family breakdown is the major suicide trigger for family men – men in their peak child-raising years from 25-44.

Here’s what the ABS said:

‘The top risk factor for males aged 25-44 years was problems in spousal relationships circumstances, present in over one-third of suicides. Problems in spousal relationships overtook mood disorders as the top risk factor in this age group for the first time and can include separation and divorce as well as arguments and domestic violence situations.’

We’re talking family law issues, men under fire in our increasingly hostile family law system, facing the risk of losing their children, home, and assets. Men who are facing the stress of monstrous legal costs. Plus we have the sad reality that ‘domestic violence situations’ often include false allegations.

Last month there were 2,500 empty shoes on the lawn in front of Parliament House representing the men who have lost their lives by their own hand this year. This powerful memorial event was sponsored by the Zero Suicide Community Awareness program which aims to educate Australia about what needs to be done to reduce these shocking suicide numbers.

Here’s a brief video giving an overview of the memorial – produced by Dads4Kids, one of the many men’s groups who came together to make this all happen.

Listen to Mary O’Brien, who runs a rural suicide organisation called Are you Bogged, Mate? O’Brien started speaking out about the high suicide rate in rural areas many years ago, pointing out how many of these blokes were driven to take their lives by family law battles. She’s touring the country speaking about rural suicide – rural men are twice as likely to take their lives as metropolitan men. Five times more likely than metropolitan women.

We lose a farmer every ten days in this country – and this crisis has led O’Brien to give up her work as an agricultural scientist to devote herself to calling out the health authorities’ failure to tackle male suicide properly. ‘Everything I read was bullsh*t,’ she says, spelling out the misguided approach being taken to male suicide.

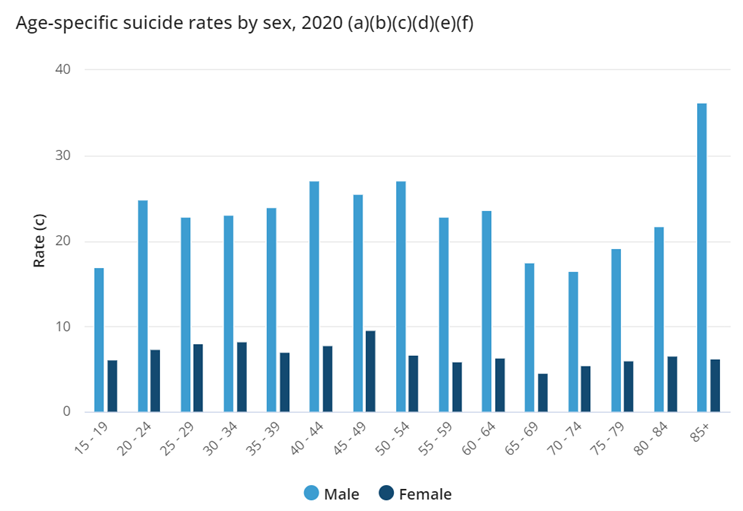

She’s also concerned about the way statistical bodies report male suicide. For example, the Australian Bureau of Statistics graph below clearly shows the glaring difference in male and female suicide rates.

The ABS highlighted this telling graph in their reports on suicide trends until 2020 when it suddenly disappeared, to be replaced with two separate graphs – one for men and the other for women. The net effect of this change in the display of data obscures the reality that suicide is overwhelmingly a male problem.

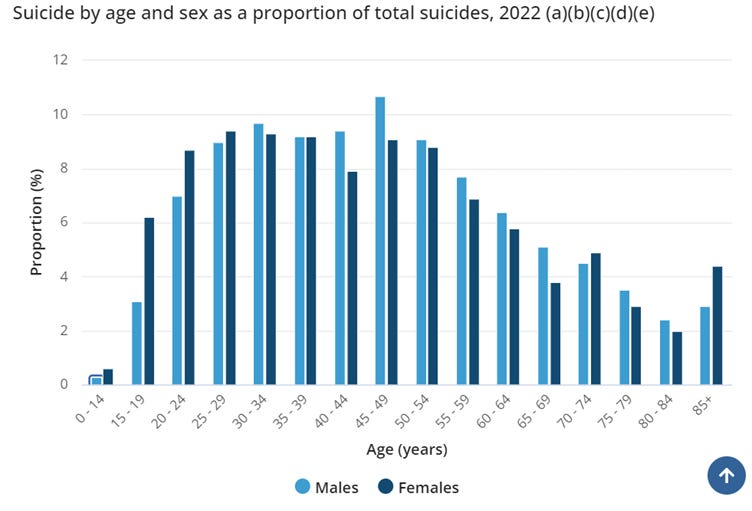

What’s left in a prominent position is this graph, where the gender split is no longer obvious.

The gender disparity has not gone away, it is obscured by the choice of display. Here, the suicide rate for 35-39-year-old males and females appears comparable when the reality is suicide rates for males are more than 3 times higher.

Instead, the suicide figures for each age group are shown as a proportion of total suicides in each gender, rather than for all suicides. Therefore, in the 35-39 age bracket, the figure of 9.2 per cent for women represents 73 individuals, while the figure of 9.2 per cent for men represents 227 individuals. The graph makes these figures look the same.

The Zero Suicide event attracted various Opposition and One Nation MPs and Senators, speaking out about the male suicide crisis. As usual mainstream media did a brilliant job ignoring the event – despite the organiser Paul Withall having sent over 1,000 emails to media groups seeking publicity.

Male suicides are 35 times as numerous as deaths from domestic violence.

How come we are willing to spend millions of dollars each year to try to protect women from domestic violence while working so hard to ignore the tragedy of all those dead men?