Since the recent Referendum, many commentators have referred to the state of play in the Victorian negotiations between the state government and Indigenous peoples. The consensus, as reported in the media, is that progress is continuing at a steady pace.

Some would say, a very satisfactory pace.

Part of the consensus is that Victoria is ahead of all other states on the road to reconciliation. Two Reconciliation and Settlement Agreements (RSAs) have been completed, the first in 2013 following negotiations by the Baillieu/Napthine Liberal and National Coalition.

A third RSA was signed in 2022 by the Andrews government. It is significantly more generous to the five Indigenous tribes who claim a special connection to an area half the size of Tasmania and currently in parts of ten Local Government areas.

The Agreements are a device made possible by a Federal Court decision in 2005 which in effect swapped Native Title protocols made in the Mabo case for a more flexible system. This enables a state government to control the processes now being used in the ‘negotiation’ of RSAs in Victoria. The 2005 Federal case was by consent of both parties which meant judicial arguments were dispensed with. The Victorian state government and Indigenous peoples’ representatives were at one with the job at hand.

If there was ever a possible conflict of interest, it was inconsequential compared with the passage of the 2018 Bill called Advancing the Treaty Process with Aboriginal Victorians. The Greens Party argued that the body overseeing the treaty negotiations must be independent of all parties to the treaty process. This was refused by the Andrews government.

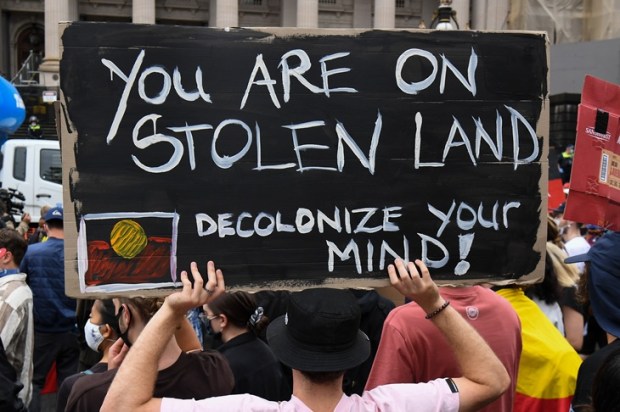

The Liberal Party queried what consultation sessions were run with non-Indigenous Victorians on the treaty process. None was the government Minister’s reply, ‘…but what I do know is that by the time that this mechanism has come into play, there will be significant community education and information about the treaty process.’ No hint of a consultative process – just the promise of an education, possibly re-education, like those carried out by a good old totalitarian entity.

To date, there has been virtually no community education. The latest RSA has been negotiated in secret for five years between state government officials and an Indigenous Land Council representing the five tribes from Victoria’s Wimmera region. It surfaced within the last four months because local governments in the area are supposed to be integral to the framework needed to make future action happen. The document could be secret no longer. In a nutshell, the Andrews government signed off on an Agreement intending local government to take an important role – but without participation by relevant Shire councils when ‘negotiations’ took place. Furthermore, all funding information was redacted. The 2005 Federal Court decision meant these Agreements do not have to be brought back to Parliament for scrutiny.

That said, during the debate of the 2018 Advancing the Treaty Process Bill, the Labor Government Minister made an admission that less than 25 per cent of adult Aboriginals had been consulted. Challenged that consultation should have been held throughout the community before the Bill entered the Parliament (which is the normal practice), the Minister said, ‘What this Bill does is it takes an emerging conversation and emerging knowledge and, I have to say … an unmet movement that has not been recognised … a movement towards Treaty … a grassroots movement.’ He said 62 per cent of the community supported this ‘movement’. This is the same 62 per cent which was recorded as being in favour of the Voice at the beginning of the Referendum campaigns – which rapidly fell to 40 per cent. Astoundingly the Minister confirmed:

‘In fact probably most Victorians are happy that they do not understand what happens in the Parliament … this piece of legislation is about allowing and supporting Aboriginal people to have a go … and we’ll see how far along this path we can go’.

Was he saying the silent bit out loud: that public ignorance is political and parliamentary bliss? A door open to political abuse. If so, his comment is as telling on all others in the House who enabled the vote.

The same Minister Jennings later argued that because ‘the resources and institutional levers that the State has are comparatively large and disproportionate to those in control of Aboriginal peoples … we are trying to design a process to remedy that imbalance in the method by which we relate to each other’. Under questioning, he admitted that how a fund would be established, who would oversee it, and how such money will be given was yet to be decided. Government by vibe sounds familiar to all Australians in recent times.

For those who sleep soundly every night trusting that Parliament is making sure a democratic system maintains fair and proper due process, they should be alarmed and shocked. Here are important matters being debated before a puff by the magic dragon suddenly is supported by every political party in the state. On a wish and a prayer, the Parliament ushered in new rules for important changes to how we are to be ruled in Victoria. That was in 2018.

In August 2022, another Bill was introduced, advancing the Treaty process by establishing a Treaty Authority.

When the Victorian Charter of Human Rights entered into the Statutes in 2006 it became law that all new legislation in Victoria had to be approved by the Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee (SARC) under section 28 of the Charter. Furthermore, the Minister responsible for every new Bill had to present to Parliament a Statement of Compatibility between the Bill and the Human Rights Charter.

In the case of the Treaty Authority and Other Treaty Elements Bill 2022, the legislation was never approved by SARC. Technically, the Act has always been in breach of the Charter of Human Rights of 2006.

If that wasn’t enough, the Statement of Compatibility was inadequate, relying on unconvincing arguments that absolved all Members of the Treaty Authority from any unlawful behaviour without knowing what that unlawful behaviour might be. In other words, the law says they can break the law. It also skipped through some sections of the Charter, whilst ignoring others more pertinent.

Section 20 of the Charter states that a person must not be deprived of property otherwise than in accordance with the law. Two clauses in the Bill setting up the Treaty Authority could be considered to deprive a person of property according to the Minister’s Statement of Compatibility.

Yet because any such deprivation would be declared ‘in accordance with law’ they will not limit the right to property found in the Charter. A triumph of bureaucratic nonsense. To have this cute twist of logic buried within the annals of history does not deny the fact that the legislation to establish a Treaty Authority was, by definition, dealing with transfers of property (public money and public land).

The people of Victoria, whose interests are supposed to be protected by the State are, in effect, being split between Indigenous citizens and non-Indigenous. When the Treaty Bill was being introduced into the Victorian Parliament, the Aboriginal Affairs Minister said that ‘through Treaty we can formalise a better and fairer relationship between government, First Peoples and all Victorians’.

Remarkably, she went on to say the Treaty Authority would ‘ensure treaty can realise positive outcomes for every Victorian … while being publicly accountable to all Victorians and culturally accountable to First Peoples’. This was called a ‘bicultural treaty process that can deliver for every Victorian’. Maybe … or maybe not. What would a Treaty deliver for most Victorians?

These lofty ideals were announced in June 2022, the same month SARC requested clarification from the Minister about the compatibility of the proposed legislation with the Human Rights Charter. Neither a reply nor a clarification was ever given.

Despite this, the matter was put to a vote and duly passed. The government had the numbers. Yet it didn’t need them because the Liberal and National Parties voted for this messy and deficient legislation except for one Upper House Member, Bernie Finn.

Parliament at its worst. Riding roughshod over its own laws enshrined in the Human Rights Charter and saying in the words of the Minister introducing the Bill, that the legislation will ‘pave the way for a better future rooted in truth, justice, equality and respect’.

The logic surrounding the deprivation of property belonging to both Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Peoples in which the property ends up in the control of only one group of persons is dubious. Even worse is the breach of the Charter’s section 7 which sets out the human rights Parliament specifically seeks to protect and promote. Clause 7 (3) states ‘nothing in this Charter gives a person, entity or public authority a right to limit…or destroy the human rights of a person’. A Treaty Authority must heed this provision even though the three Agreements signed by the State Government with Indigenous peoples have not.

Another important provision in the Human Rights Charter is in section 15 providing for every person’s right to freedom of expression. This includes the right to hold an opinion without interference. How does this work in a Treaty controlled by one party over another, and a larger number of non-Indigenous people who have been in the dark about the terms being negotiated?

The similarities between the handling of the changes proposed for the Indigenous peoples of Victoria and the poor management of the Federal referendum on the Voice are there for all to see. Withholding information is never the smartest way to convince the public about change. Worse still is the cruel method of giving false hope to an important group in the fabric of what we share in Australia.

On November 3, 1999, a member of the Victorian Parliament declared their belief, first and foremost, in equality and the role of government to give all people equal opportunities. ‘As members of Parliament, we are the servants in our electorates. With must communicate with them in an open and intelligent manner, not isolate them from the political process.’ That person now is Premier.

Can we assume she hangs her head in shame when she assesses the processes today in the Victorian Parliament, groping in the dark to adhere to sound parliamentary practice?

Many of us can’t wait to have the integrity or lack thereof, explained when the public is given the opportunity to know what in the world is going on.

They might be surprised to learn that in that same maiden speech in 1999, the now Premier said, ‘Country Victorians believe in democracy, and they will not tolerate being taken for granted or treated as second-class citizens.’

Nearly 20 years later, such words were mocked in the Parliament by her colleague, Minister Jennings, with his ‘public ignorance is political bliss’ sentiment of 2018 in relation to the formulation of Indigenous-related legislation.

It illuminates how wide is the gap between the government’s attitude to the electorate and to proper, lawful, parliamentary procedure. All Victorian MPs must share the blame for diminishing basic integrity.

Roger Pescott, Former Minister in the Kennett government