Remember how the Brittany Higgins case blew up when a juror brought into the jury room an academic paper discussing the frequency of false allegations of sexual assault? That broke the rules prohibiting jury members from accessing outside material relevant to the case.

Yet the significance of this extraordinary event, which led to the mistrial of one of Australia’s most sensational rape cases, has passed largely unnoticed.

The myth that women hardly ever lie is a central plank of the feminist mythology about sexual assault which now underpins our justice system. That makes it absolutely vital for feminists to maintain the fallacy that false allegations are statistically extremely rare.

Boy, have they done a great job in promoting that mistruth. The mantra that false allegations hardly ever happen lurks as a dangerous subtext in sexual assault cases hitting the courts in Australia.

Bruce Lehrmann’s lawyers are currently preparing for next month’s defamation battle against Network 10, Lisa Wilkinson, and the ABC over their coverage of the criminal case last year. But still, The Guardian ran the the headline Network 10 lawyers seek to use evidence on rarity of false rape complaints.

But what about that evidence on the rarity of false complaints? Often you will hear repeated that a piddling 5 per cent of rape allegations are found to be false. That’s the party line and you’ll find it promoted everywhere.

Look at this extract from a fact sheet giving the Victorian Police’s advice on misconceptions about sexual offending:

‘Guys, you can stop worrying about false rape allegations. They’re extremely rare,’ trumpeted the ABC’s Hack program, pitched at young people. Only 5 per cent of reports are false, they explained.

The Sydney Morning Herald recently pronounced that we do not have a major problem with men being falsely accused of sexual assault, claiming ‘statistics show false complaints of sexual assault are incredibly rare – a 2016 meta-analysis of seven studies of rape allegations in four Western countries put confirmed false police reports at 5 per cent.’

They’re all singing from the same songbook but that’s just been shot full of holes. Finally, that famous meta-analysis has been subjected to proper scrutiny – and the data actually reveals false allegations are far less rare than is commonly claimed.

And this is all courtesy of two Australian researchers, Tom Nankivell and John Papadimitriou, who have expertise in statistical analysis and public policy, and more than three decades of experience each as researchers and policy analysts with various government agencies. They conducted a review, titled True or false, or somewhere between? A review of the high-quality studies on the prevalence of false sexual assault reports, in which they analysed the methods and data reported in often-cited statistical surveys of the prevalence of false allegations, undertaken in various countries.

This research was recently highlighted by Oxford criminology researcher, Ros Burnett, who described the Nankivell/Papadimitriou review as ‘an important and overdue study’ commending the authors for bringing ‘an empirical approach and unrhetorical tone to the discussion’.

Ros Burnett’s discussion of the Australian researchers’ review, published last month in The Justice Gap, suggests the Ferguson and Malouff meta-analysis, which came up with the much-promoted 5 per cent false allegation rate, aggregated the findings of statistical studies that ended up largely ignoring categories of cases likely to include false allegations.

In counting up false allegations, the studies only included cases where the complainant admitted the allegation was false, or where police found strong evidential grounds to assume she (or he) had made it up or had been mistaken. That meant excluding all cases where there was insufficient evidence to prosecute, or where the complainant withdrew the allegation, or where the accused was tried and acquitted. None of these cases were included under false allegations! In addition, at least one of the studies included basic mathematical errors while others relied on very limited data.

With this highly dubious culling of the data, it is no wonder such a low rate of false allegations was reached. Nankivell and Papadimitriou laboriously re-examined the original data to include estimates of possible false allegations in these excluded categories. They concluded that, ‘…even with reasonably modest assumptions about the actual level of false allegations in other categories, the prevalence rate for the studies sample would easily exceed 10 per cent and could approach 15 per cent.’

Note this is the conclusion from two very conservative, quantitative researchers. What’s the bet the real rate is actually far higher? According to a recent YouGov survey, 19 per cent of Australians know someone personally who was a victim of false accusation of sexual abuse or rape.

The Nankivell/Papadimitriou report is vital information, necessary for putting the record straight about this critical statistic which is being used to shut down debate on false allegations and undermine the chances of a fair hearing for accused men.

Please help make sure people know about this study. It is important that news of this path-breaking analysis reaches decision-makers in our police force and justice system, lawyers, journalists, and everyone complicit in promoting the feminist myth that false rape allegations hardly ever happen. Here’s the best link to use to circulate the study.

In her article examining this research, Ros Burnett discusses her own work for over a decade as a criminologist looking at wrongful allegations – she’s the editor of an excellent book, Wrongful Accusations of Sexual and Child Abuse. Burnett describes the hundreds of cases she has encountered where individuals have been found to be falsely accused and her frustration when such cases are dismissed as ‘extremely’ or ‘vanishingly’ rare. She has been personally accused of ‘being an apologist for rapists’.

That’s the climate we live in, where anyone with the courage to tell the truth about what’s really going on end up attacked. Men are being falsely accused of rape in this country – I am in touch with two tragic cases of young men jailed in the last few weeks following absurd allegations which should never have ended up in court.

Nankivell and Papadimitriou rightly make the point that ‘there is no credible evidence that women routinely fabricate sexual assault claims’ and that ‘the majority of sexual assault reports are true’. But what also muddies the waters is the massive expansion of the type of behaviour now classified as sexual assault. There’s a steady stream of cases now finding their way into court that involve young couples, where a girl may suddenly decide that she hadn’t given consent on one occasion after having sex when she was half asleep, or pretty drunk, even though they might have done this dozens of times before. It makes no sense.

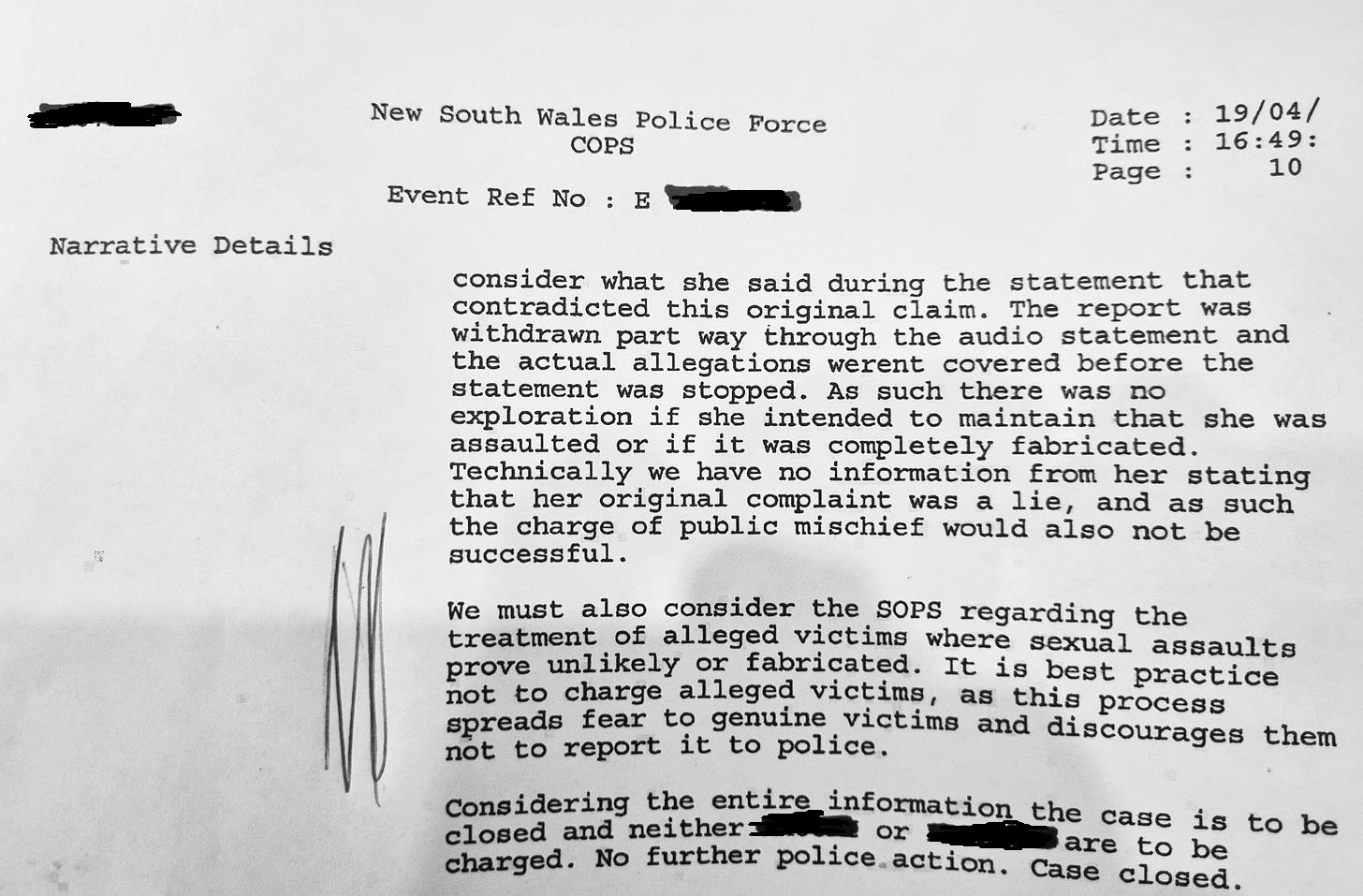

To return just briefly to that meta-analysis of statistical studies which relied mainly upon cases where police found ‘strong evidential grounds’ for false allegations. The police have a huge disincentive to identify and confirm such grounds because they appear to be under instructions not to take action over false allegations. I’d long heard from families of accused men and also from police about these instructions. Lo and behold, I recently received proof in the form of a case note from the NSW Police Force referring to this standard operating procedure in a case where no action was taken with a likely false accuser. Here it is…

Here we have a case that apparently fell apart, where the police were left unsure if the whole thing was ‘completely fabricated’. But they followed orders not to properly determine whether there were the required ‘strong evidential grounds’ to charge the woman. Another man and his family, put through the horror of a possible rape trial, the public humiliation, shaming, the financial stress of seeking legal help. Another woman gets off scot-free.