Part One. The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1971) The first Barry McKenzie film was, as everyone knows, based on a scurrilous comic strip about the adventures of a gormless Australian in London. As outrageous and even unbelievable as the events were, many of them were based on the actual adventures of Barry Humphries during his early years in the city.

I was working at the British Film Institute from 1966 mostly producing low-budget films by first-time film makers – a scheme devised to find a way around the sinister film union, the ACTT; a group that had devised the mysterious tactic of forbidding people to work in the film industry unless they were union members but, cleverly, simultaneously denying membership unless the applicant was already employed in the industry.

Back in Australia a fund had been set up by the government to encourage film production. I suggested to Barry that we write a film script adapted from the McKenzie strip, then send this to the Film Commission back in Australia for finance. Barry was at first wary of the idea but warmed to it when I pointed out he would have a major role if we wrote in Edna Everage as an aunt of Barry McKenzie.

Barry went back to Australia on tour with one of his stage shows. He met Barry Crocker and Phillip Adams, both of whom turned out to be crucial for the realisation of the project. Barry Crocker could sing and also had a prominent chin – just like the Barry McKenzie of Nicholas Garland’s drawings. Phillip Adams was the key figure in persuading the cautious committee members of the film commission that a film full of Australian slang, sexual innuendo and a cheerfully irreverent story line, plus a director (me) who hadn’t ever made a feature film, was a sensible investment as one of their first feature film projects.

Our $250,000 budget was approved. At Sydney airport as Barry Humphries and I were leaving for London to begin the shoot a frantic phone call came from the head of the Australian Film Commission imploring us not to include any Australian slang or euphemisms in the film. A difficult request as the script consisted of little else.

The Adventures of Barry McKenzie was shot in four weeks, in London in mid-winter. I remember that the days were so dark that the cameraman, Don McAlpine, complained of not being able to get an exposure at mid-day. (McAlpine later achieved worldwide celebrity with Breaker Morant, My Brilliant Career, Romeo and Juliet, etc etc.) The film was popular when released and still is, over 50 years later. Film critics did not participate in the general enthusiasm as they castigated it for vulgarity, even labelling it ‘anti-Australian’!

Part 2. Barry McKenzie Holds His Own (1974) Despite the popularity of The Adventures of Barry McKenzie my directorial career showed no signs of life. The hostile reviews branded me an irretrievable low-brow.

I was anxious to make a film of Henry Handel Richardson’s short novel, The Getting of Wisdom, and approached the TV mogul , Reg Grundy, for finance. Grundy had achieved fame by going to South Africa as commentator on a world title fight but failed to find the boxing stadium on the night of the event so his non-existent commentary terminated his radio career. Enterprisingly, he shifted to producing quiz shows, most of them based on American shows he’d seen while staying in a motel in Los Angeles. These were wildly successful so the Grundy empire was flourishing.

Grundy’s enthusiasm for The Getting of Wisdom was limited but he agreed to finance the film if Barry Humphries and I first made a Barry McKenzie sequel. He suggested Barry and I go somewhere quiet and write a script. After some discussion we decided on Launceston – for some reason I no longer recall. We settled into an attractive motel and would meet at 9.30am, work on the script to lunch, have a nap, then work again to 6.30pm.

Being a touch-typist I would bash away at the keyboard (a typewriter keyboard, this being 1966) as Barry came up with most of the script ideas – which invariably displayed his fascination for old horror films and an array of bizarre characters. A couple of ribald songs were included for Barry Crocker.

Despite some sleuthing, there were no diversions in Launceston that we discovered although I vaguely remember going on an aerial ride in a chair suspended over a river. Barry declined this adventure.

During lulls in our writing, as we struggled toward a new scene or sparkling dialogue, our conversation ranged erratically over other topics – mostly stage shows and films, writers, composers, painters and people we liked or detested. Politics were rarely discussed. I’ve often read that ‘Barry Humphries is very right-wing’, a label that I’ve noticed tends to be fixed to anyone who doesn’t unquestioningly accept the latest left-wing fixation. I never heard Barry express admiration for right or left wing idols/dictators. One day, during a temporary writer’s block, he fiercely condemned the Australian governments unforgivable policy in relation to the immigration of Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazis in the 1930s. The number accepted was restricted to a small quota and the only people eligible were those who could pay a fee

One day we ran into a woman in the street who Barry had met after one of his shows some years previously. His astonishing memory sprang into action as he amazed her by recalling the name of her husband and the names of her children.

Reg Grundy calmly accepted my budget of $750,000 so we set off to locations in London, Wales and France – where we coolly filmed at Versailles without permission.

Probably because of the devastating reviews of the first film, there was no marked enthusiasm among actors to take our key supporting roles but Barry persuaded various friends to appear; including Donald Pleasence, Dick Bentley, Ed Devereaux and John LeMesurier. I recruited three friends from Sydney Uni, Michael Newman, Clive James and Brian Tapply. Someone, probably Phillip Adams, induced both John Gorton and Gough Whitlam to play themselves in brief appearances. Gorton was quite hostile during the filming, no doubt considering his appearance a tactical mistake, but Whitlam seemed to enjoy the process, even suggesting he make Edna Everage a Dame.

The second Barry McKenzie film was as popular as the first one. The box office returns didn’t compare with the bonanza of the quiz shows so Reg Grundy declined to finance The Getting of Wisdom. Once again my career languished because of the critics’ hostility, this time provoked even further by the film’s outrageously offensive title. I returned to London to direct a dismal rock musical that I’ve managed to keep from appearing on my CV. After a few months, I was rescued by Phillip Adams who contacted me to see if I was interested in making a film of David Williamson’s play Don’s Party. I leapt at this, not just because I was out of work, but because I thought the play was outstanding with acutely observed characters and often very funny. Don’s Party was quite a success, so, once again, I looked for finance for The Getting of Wisdom.

Part 3. The Getting of Wisdom (1977)

Barry Humphries had no input with the script of this film. The adaptation of Ethel Richardson’s memoir of her Melbourne schooldays in the 1890s was written by one of Australia’s major eccentrics – Eleanor Witcombe. Alert and quick-witted, she was incapable of (a) finishing the script and (b) reducing the immense verbiage of the scenes she had written. I did a major editing job on the screenplay and Phillip Adams once more flew to the rescue, somehow finding finance for the production in Melbourne.

The cast was mostly teenage schoolgirls A major casting problem was to find someone to play the headmaster of their school. I optimistically sent the script to James Mason in England. There was no reply. No doubt he was wary of a film in Australia with the offer of a paltry fee and an unknown director. Laurence Olivier also failed to respond.

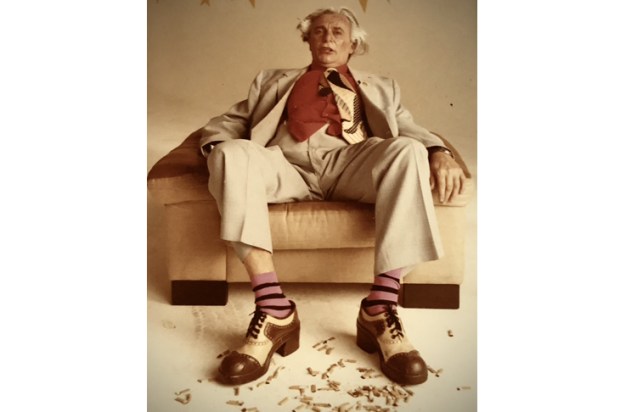

Some other names were suggested and discounted when it struck me that Barry Humphries would be ideal. Phillip Adams and a couple of co-producers were hesitant as he was known principally for his comedy roles on stage. I protested, stressing that he was a great actor and had already created characters such as the elderly Sandy Stone, who I found very well observed, realistic and moving.

Once I had a degree of rather cautious agreement I called Barry about the film. He was in England and I wasn’t surprised that he knew the novel and its characters. He agreed to play the role, probably out of friendship. He certainly wasn’t desperate for the modest fee.

Back in Melbourne, Barry moved into the Windsor hotel, where we spent a few days rehearsing his scenes. My only direction was a comment I’ve made to many actors – ‘straightforward and as simple as possible’.

The filming was nearly all at superb Edwardian locations in Melbourne, where both Barry and John Waters (playing a parson) clearly relished being surrounded by a cast of very attractive young women. Barry was one of those actors who could slip totally into the character he was playing, do the scene, then effortlessly resume a conversation he was having as Barry Humphries. (Much easier for a director to handle than a performer who boorishly insists on ‘staying in character’ once ‘Cut!’ has been called.)

I was proud of the finished film and thought that Barry played his role with insight and without a touch of caricature. The critical reviews were tepid as two other films with similar period settings, Picnic at Hanging Rock and My Brilliant Career, eclipsed The Getting of Wisdom. Sadly, I made no more films with Barry, although I sought his advice and knowledge about the painters William Orpen and Frank Brangwyn for my documentary, An Improbable Collection (2021).

We remained in constant touch until his death a week ago. I revelled in his brilliant conversation, his warmth, his kindness and his astonishing wit.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.