It is possible the Albanese government decided one national discussion was enough. Rationalising that Australians’ concerns over the Voice would trump Australians’ concerns about how their taxes for the next umpteen years would service the $368 billion cost of the Aukus submarine plan, Labor decided to have a controlled discussion of the former and give no public forum to the latter.

Commentary in Australian newspapers on the Aukus submarines swings like the proverbial pendulum. It moves from being an eye-watering expense that, if ever realised, runs the danger of being implemented too late to be a wise policy (which allows Australian trade with China to get back on track), but at the same time sends a clear message of where Australia stands on Indo-Pacific geopolitics.

No one expects the press in a democratic country to run the same argument, but perhaps more open discussion of how taxpayers will have their money spent would make for a better understanding on the part of Australian readers. Instead of feeling like the clown patiently turning its head to catch the elusive ping pong ball, Australians who keep abreast of our foreign policy initiatives could perhaps enjoy a clearer view of what the discussion, if we ever had it, might be about.

But what if the government, or worse, nobody, knows the full context in which the discussion might take place?

Some say China’s wolf-warrior is a thing of the past, that China does not intend to threaten Australia and would, even if China did wish to, be unable to threaten Australia. Others feel China is flexing its muscles, especially over the question of Taiwan, and is biding its time before it decides to reclaim the country it believes belongs to it. In March of this year, China announced a yearly defence budget of RMB 1.55 trillion ($224.8 billion), an increase of 7.2 per cent on the previous year’s defence budget. Add to this the suspicion that the official budget is one thing, and how much China actually spends on its military another, and the amount could be even higher.

A claim that is often made about China, and sometimes rather grandly the Chinese people in general, is that they have their eye on the long-term game. It is an argument that sits well with the Confucian philosophy that dominated Chinese society from the fifth century BCE until the communist revolution and then, uncoincidentally, the communist ideology which supplanted it. Short-term gain, read individualism, is still the mainstay of the West and stands no chance against a philosophy that is prepared to bide its time and wait for its chances. Whilst the West whips itself up into a state over minor details, China rolls along relentlessly keeping its eye on the prize.

This is all relatively plausible except no one knows what that prize is. Is it to supplant American hegemony and, in the terms of some cheap political thriller, to take over the world? And if so, how exactly would ‘taking over the world’ manifest itself? Tributary states were how the Qing Dynasty, who ruled from 1644 until 1911, showed its control over its neighbours. Countries like Korea and Vietnam were allowed some independence providing they recognised the superiority of their larger neighbour by bringing tributes to the Qing emperor which he would deign to accept. It was not trade because as Qian Long politely pointed out to the British when they arrived at the end of the eighteenth century hoping to trade: ‘We possess all things.’ A silver lining to counteract fear of China’s flexing her military muscles is that this is not the case today.

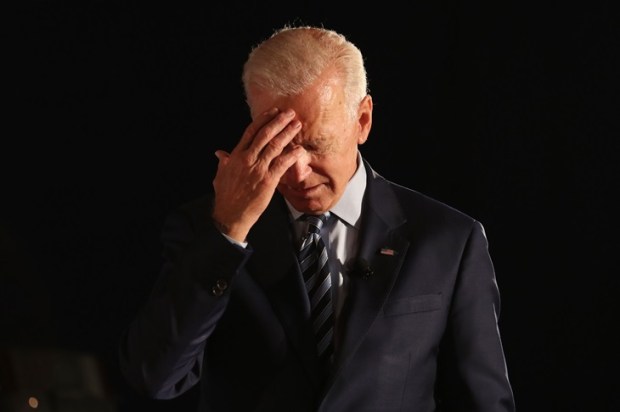

We can only tell what China wants from what China does. Decisions to buy into Aukus were made when, as punishment for Australia’s megaphone diplomacy over the Covid outbreak (possibly at the United States request – the question not the megaphone), Australia lost an estimated $20 billion in trade with China. For too loudly suggesting this investigation Australia was described in the Chinese Communist Party-run Global Times as, ‘chewing gum stuck on the sole of China’s shoes’ and that ‘sometimes you have to find a stone to rub it off’. It was this economic punishment, and it was these words in particular which encouraged the Liberal and the Labor government to strengthen ties with our erstwhile ally the United States. Whether the United States will stick to the agreement, an increasing concern if President Trump is re-elected, is a risk both the Morrison government and the Albanese government have decided to take. For us.

Perhaps given the decisions which have been made, when it comes to foreign policy governments should be bipartisan and if so, then take a leaf out of China’s book and learn to play the long game. Perhaps we should keep our eye on the prize. And given our circumstances we don’t need to wonder what that prize is, our economy has been reaping the benefits of it for the last two hundred and thirty-five years.