In today’s world, government spending accounts for up to and (in the EU) over 50 per cent of GDP – Australia’s at 38 per cent may be understated due to it being a federation. In the 1920s, no significant government spent more than 20 per cent of its nation’s GDP (federal spending in America and Australia was 4 per cent 6 per cent respectively).

Sovereign debt is now well in excess of 100 per cent of GDP in most EU countries, America, and Japan – Australia’s is 57 per cent. Until 100 years ago no state went into debt except to combat an existential crisis – indeed few states had the creditworthiness to do so.

British government debt, following the Napoleonic Wars, reached some 250 per cent of national income and strenuous efforts were made to repay it by reviving the ‘sinking fund’ payback concept of a century earlier. France’s indebtedness from its wars with England brought about the events that led to the Revolution in 1789. American debt rose to as much as 40 per cent of GDP after its wars (Independence, 1814, Civil War, and the first world war) but was largely paid back in the years following.

The abandonment of rational economics – small government and a balanced budget – is associated with Keynesian economic theory developed in the mid-1930s.

Keynes dignified the practice of budget deficits by arguing that up to a point (that is until public spending reached a then stratospheric 25 per cent of GDP) government could inject funds into the economy, thereby stimulating demand and recouping those funds once the economy returned to normality. The objective was to iron out the swings which were seen in the 1920s and 1930s and prevent unemployment and premature scrapping of investments. The process depended upon ‘money illusion’ tricking consumers into increasing their spending, thereby stimulating investment and recouping the spending as the interventionary policies returned the economy to its underlying growth path.

It is doubtful the process ever worked even in the limited role Keynes envisaged.

But modern governments are ever keen to increase spending to win votes from an electorate that sees no relationship between lower income levels and high spending with budget deficits. This has found its apogee in ‘Modern Monetary Theory’, which argues that the economic benefits of government spending are limitless. Though the notion is absurd and scoffed at by establishment economists in Treasury, the RBA, and elsewhere, in reality it describes current budgetary practices in Australia and most other developed nations.

Determined spenders will always find Keynesian economists who will verify that any broached spending measure will bring positive feedback. Thus, governments claim net benefits from ‘investing’ in childcare, hospitals, regional initiatives, rail infrastructure, and more, most of which have gross benefits but all of which also means more taxes or debt that eliminates the net benefits.

Policy departures from well-grounded rational economics are not limited to spending measures.

For many years, most Western governments have been following policies that subsidise wind and solar energy, hence imposing discriminatory taxes on established forms of energy from fossil fuels. This process began 20 years ago when John Howard bowed to the clamour for interim support to enable the ‘infant industry’ of wind-generated electricity to reach competitive maturity. An initial requirement that 9,600 gigawatt hours (nominally two per cent of electricity) be supplied by renewables was increased to 41,000 gigawatt hours plus unlimited roof-top solar under Kevin Rudd, before being reduced by Tony Abbott to 32,000 gigawatt hours but with roof-top solar left untouched. Subsidies to these facilities garner a greater level of regulatory funding than large-scale wind and solar.

Solar power now accounts for over a fifth of electricity supply, all of it subsidised through regulations and direct support which amounted to $7 billion in 2020. New measures are being introduced, including a fourfold increase in transmission to cater for the dispersed nature of renewable supply, together with support for batteries and pumped hydro to compensate for its irregularity.

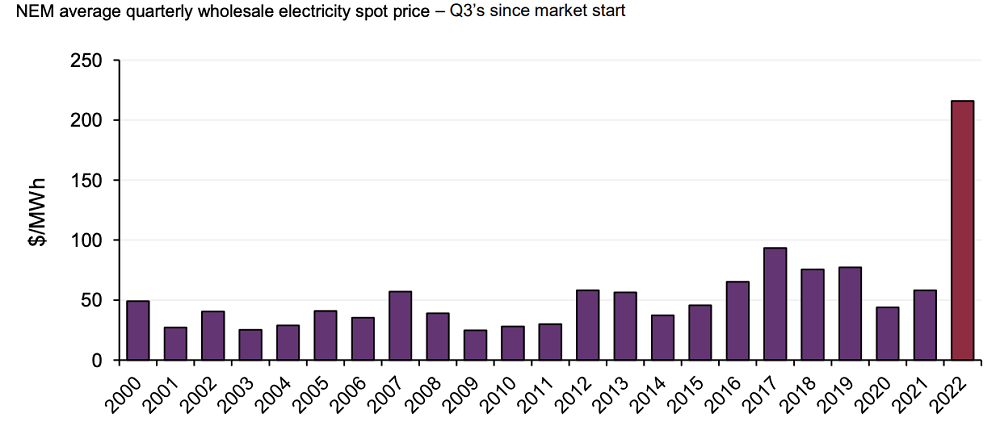

The upshot has been price increases as shown below

While some of this is attributable to the Ukraine War, this does not apply to the 65 per cent of supply from coal hardly any of which (and none of Victoria’s brown coal) is exportable.

Government policies have demonised coal, prejudiced its competitive position against renewables, amplified its costs through taxes and regulations and prevented the development of new gas supplies. This has brought the present high prices and even concerns about electricity and gas supply availabilities.

Given the retreat from rational economics, it is not surprising that governments are in denial about the adverse consequences of their actions. Hardly less surprising is that their response to a shortage of supply is to increase the tax upon it – even apparently upon the gas and coal that is exported either under contract or because it cannot be delivered to domestic users!