Have we learnt anything from our past experience of infectious disease?

For well over a century, pandemics and epidemics produced fear and havoc in Australia – becoming recognised as one of the most severe of all threats facing the country. Today, Covid is still in Australia, so too is Influenza, Dengue, Ross River Fever, Barmah Forest Virus, Q Fever, and Leptospirosis, as well as a host of childhood infectious disease agents such as Chickenpox, Measles, Rubella, and Bronchitis. We also continue be confronted by a range of international threats from diseases such as Ebola, Zika, Malaria, Lassa Fever, TB, and a range of other infectious diseases.

Without any doubt we have not won the battle to eliminate or control infectious disease. Covid may quite likely usher in a new Age of Pandemics. But are we really prepared to confront another major era of infectious disease? I very much doubt it.

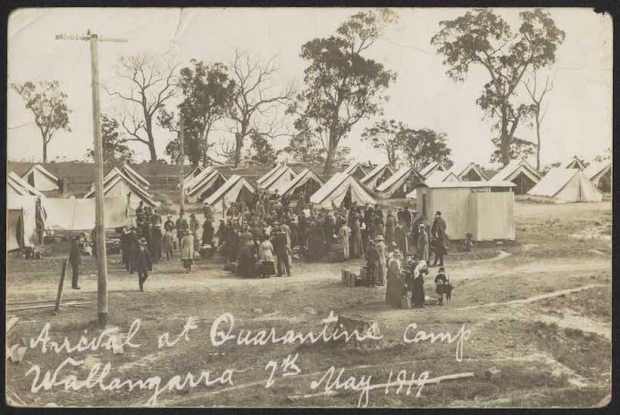

Australia’s history is simply littered with pandemic and epidemic outbreaks. Since the early days of settlement, Australia has experienced at least 22 pandemics and more than 30 major epidemics. Some of these were life-changing events such as Bubonic Plague between 1900 and 1909, Influenza in 1891 and 1919, Smallpox 1881 and 1913-17, Polio 1903-56, Dengue 1925-26, HIV/AIDS 1982-2011, SARS 2003, and Covid in recent years.

How best to prepare Australia for another 20-50 years of epidemic and pandemic disasters is a question the government should be addressing, particularly as there is plenty of evidence to show how our government has struggled to confront major disease outbreaks over the last 150 years and how little confidence most Australians have in the government’s ability to protect them.

In many ways, the threat of older infections or the emergence of new ones reflects the fact that we continue to overlook or misunderstand the significance of the biophysical environment and that many infections are zoonotic in origin. We also continue to believe that Australia’s distance from much of the world offers protection against the spread of infectious disease. In addition, we still do not have an excellent disease surveillance system and our hospitals and healthcare facilities are not designed to handle major disease outbreaks. They do not have enough beds, respirators, or trained public health staff. In addition, as our history shows, we also often face the dilemma of sStates fighting among themselves as well as electing to go their own way during pandemic and epidemic outbreaks.

Over the last 70 or so years we have seen a shift in human affairs from a nation-state focus to a vast theatre of an international human world. The denationalisation of our health has transformed Australian health and changed the nature of infectious disease threats. Globalisation has rendered the national insignificant and replaced it with the international. Today in a highly mobile interconnected world infectious diseases recognise no national boundaries and move with ease around our world. Add this to a highly mobile world where tens of millions move around the world every year many from and to Africa and Asia. Australians are also travelling much more frequently and much further than in the past, often to places in Africa and Asia. Over the last 70 years, travel by air has become commonplace. In 2018 the global airline industry reported 4.3 billion scheduled passengers. Many airline travellers who had been exposed to an infectious disease could travel showing no symptoms during the flight or on arrival.

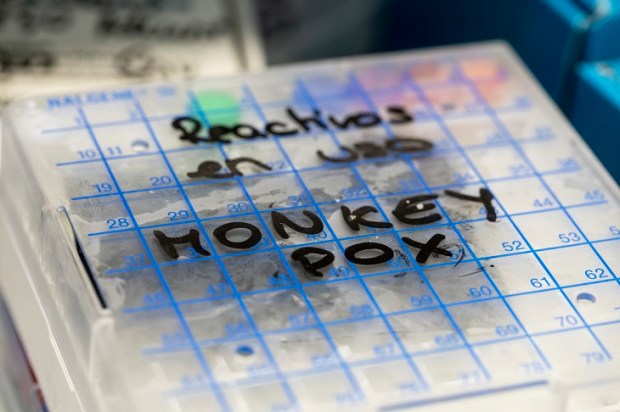

Risks from bioterrorism if somewhat unpredictable also remain a threat. The current technology supporting bioterrorism has exploded over the last 25 years and has provided a host of new biological weapons for some countries to hold in reserve. The Soviet Union is known to have large amounts of the smallpox virus as well as other disease agents in its bio-weapon program although it claimed to have destroyed all such stock in the late 1980s. Many remain highly sceptical that all were destroyed. Al Qaeda is also known for large-scale bio-weapons program in Afghanistan and North Korea is also thought to have as biological warfare program.

There is also little doubt that we continue to overlook the fact that we currently inhabit a world where a range of demographic, political, social, economic, climate, and biophysical factors greatly influence our vulnerability to outbreaks of infectious disease. Things such as population density, population growth, urbanisation, increasing mobility, ageing, as well as a range of ecological factors governing our interaction with the natural world, including agricultural development and deforestation together with flooding and temperature changes, interact closely with our government’s ability to prepare for, and react to, major disease outbreaks. Flooding also raises the possibility of major disease outbreaks, particularly when the flood water begins to recede and pools of stagnant water can lead to important breeding sites for mosquitoes to breed ultimately producing outbreaks of Dengue, Rift Valley Fever, Ross River Fever as well as a number of other diseases.

When we look at infectious disease in our world today, where are the most vulnerable countries? Most are located in Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in Haiti, Afghanistan, and Yemen. A solid contiguous belt stretches from the edge of West Africa through Sahel countries to Eritrea and Somalia and also includes parts of the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola, Malawi, and Mozambique. All these countries are characterised by poor access to resources, poor governance, weak health systems, and many are located close to remote forest areas home for a wide variety of wildlife. Human interaction with such wildlife, either for food, during urban expansion, or during times of civil unrest, heightens the risk of infectious disease spreading.

Does all this serve up a major threat to Australia and are we likely to experience new infectious diseases originating from parts of Africa over the next 20-50 years? Will this mean another pandemic phase for Australia and critically, could we rely on our government and the associated health agencies to protect us? Given our past experience, these are important questions.

Peter Curson, Emeritus Professor of Population and Health