London

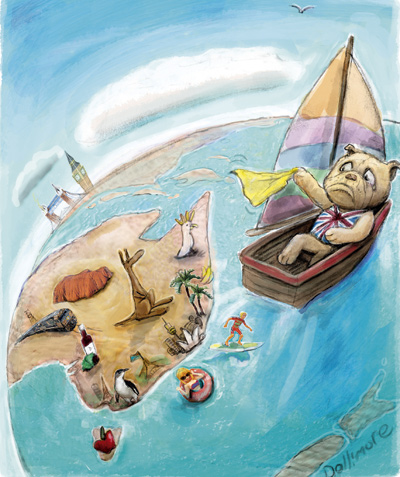

There is a risk inherent in trying to identify differences in the sporting cultures of two such apparently similar countries as England and Australia, but let us try to identify one of them at least. I sensed in the locust years of English cricket, from 1987 until 2005, that the Australians felt there was a moral force in the repeated beatings they were giving England. You served us right, and would continue to do so until we made the effort of will and perfected the physical accomplishments to allow us to beat you.

The English, by contrast, rather regret the demoralised and defeatist performance that the Australians are currently turning in. Trent Bridge was close, but only by the fluke of Ashton Agar’s astonishing innings. Lord’s, however, was an obliteration. The Australians looked ragged, riven and factionalised — and the word from the dressing room was, indeed, that they were.

The English know that the deep-seated belief Australians have in themselves as a sporting nation will in time be enough to make their cricket team strong again. The main regret is that this series, on the showing at Lord’s, may not prove especially competitive. There are more in England than the Australian public might imagine who relish good cricket, whoever is providing it, and who share the old-fashioned belief that the best man should win. That is why we sincerely saluted Bradman, Lillee, Border and Steve Waugh, and how we coped with nearly two decades’ humiliation in Ashes series.

But as we survey our wealth of new talent, exemplified by Joe Root, we regret too that the next Ashes series in Australia is to follow directly on from this one, without giving our opponents the time to recover from what many English pundits predict is the thrashing they will receive throughout the present series.

That piece of scheduling is typical of the lack of intelligence, and the central role of money, in the game. England against Australia is regarded as the golden egg whose mother goose cannot be killed. Some of us are not so sure. Contests between England and Australia may attract a keen following for some series to come, but, elsewhere, how long can the five-day match continue?

Around the world the public appetite for it is declining. In countries where the game is wealthy enough to sustain it the public is moving to other versions of the game — typified by the T20 obsession in India. When England played in New Zealand six months ago, it was to largely empty grounds. When they play in the West Indies, the grounds are full, but of lobster-coloured English tourists overdoing their suntans and lapping up the rum punches.

Elsewhere, contracting attention spans, the lowest common denominator and the insatiable greed for money mean the shorter forms of the game are racing ahead in popularity. Such is the saturation of international limited-overs cricket that its novelty will wear off in time. Whether the five-day game — Ashes series included — will survive long enough to have a resurgence is highly debatable.

As I sat at Lord’s, I saw a crowd predominantly of men aged between 40 and 80. Youngsters were few and far between. That was partly because of the exorbitant cost of a ticket, and partly because live Test cricket is only shown on subscription television in England now and has, as a result, lost some of its following, and struggles to win new fans.

The next generation of cricket-watchers and players here are busy with their computer games and other related vices. Fewer and fewer schools now play the game and chances for boys to learn it are scarce except among elite fee-paying institutions. Some parts of the country have a good structure of youth teams; some do not. County cricket in England has become deeply unappealing. Played over four days instead of (as was the case for more than 100 years) three it is often slow and turgid, and its audience has shrivelled.

Worse, a county’s best players are under contract to England, and with seven Tests each season plus one-day internationals, plus the cult of ‘resting’, some hardly play for their counties at all, which further alienates the punters. And as the counties therefore become more and more dependent on subsidies from the England and Wales Cricket Board, their financial soundness diminishes. Their future — and the future supply of England players — is accordingly under threat. It may not look like it from the size of the ecstatic crowds at Lord’s, but cricket in England too is a game undergoing a severe contraction.

There is also the question of the moral state of the game. When Stuart Broad refused to walk at Trent Bridge when he knew he had hit the ball, the cynics were out in force. Why should he walk when plenty of others don’t? We might best call this attitude a state of immoral equivalence. It comes back to the point that the game is now all about money, which is why to many of us it has become so unattractive.

Some like to point sniffily at the way the Indian one-day game seems to exist largely for the benefit of bookmakers, but enough cricketers from the mother country are ken enough to get out there and put their snouts in that particular trough. No cricketing culture anywhere in the world can claim any sort of moral superiority.

Money, too, is why there was the call in the first place for the decision review system, agreed in 2009, and why it has proved so controversial in operation, not least in this present series. Human error is a crucial part of cricket. Either there should be no DRS, or umpires should be replaced by robots. I, and I suspect most cricket lovers, would prefer the former. It is less of a game for the attempt to eliminate the human element; the pace and nature of the game have changed for the worse, and umpires (some of whom do not seem terribly sharp to begin with) now find themselves routinely undermined.

Cricket is the perfect game for nostalgics, and a series between England and Australia is the most nostalgic of all. The decline of Australia in this series has, I fear, come to serve as a mask for the decline of cricket, and of what Marylebone Cricket Club calls the Spirit of Cricket. If the spirit fails to survive, the crowds will go once and for all, at least from the serious game. If those who run, or think they run, the game want to sustain that spirit, then their greed, and their stupidity in sacrificing so much of cricket’s culture to that greed, had better swiftly be held in check. Soon, and however exciting this and other Ashes series are, cricket as we know it will have reached the point of no return.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Simon Heffer is political columnist of the Daily Mail and author of several books, including most recently Strictly English: The correct way to write … and why it matters.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.